Steel touches almost every industry you work in. Buildings, cars, ships, appliances, energy infrastructure—it’s everywhere.

Here’s the thing: most professionals I’ve worked with can’t explain the difference between the two main steelmaking methods. They don’t know why one steel costs more than another, or what actually determines quality. That knowledge gap leads to poor sourcing decisions and missed opportunities.

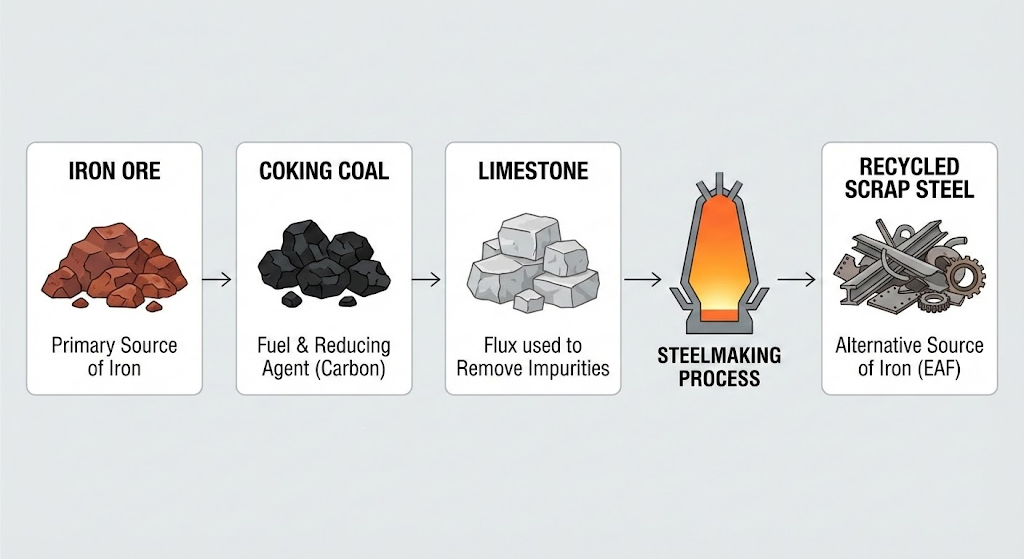

Steel production relies on four essential inputs: iron ore, coking coal, limestone, and recycled scrap steel.

Iron ore provides the iron atoms that form the basis of steel. The two most common types are hematite (up to 70% iron content) and magnetite. About 98% of all mined iron ore goes directly into steel production.

Coking coal (processed into coke) does double duty. It provides the carbon needed to reduce iron ore to metallic iron, and it generates the intense heat required for the process. Coal currently supplies around 75% of the steel industry’s total energy demand.

Limestone acts as a flux. It binds with impurities like silica and sulfur during smelting, forming slag that floats on top of the molten metal and can be easily removed.

Recycled scrap steel is the industry’s secret weapon. Steel is the most recycled material on the planet—with recycling rates averaging 85% globally. Every tonne of scrap used saves 1.4 tonnes of iron ore, 740 kg of coal, and 120 kg of limestone.

The amount of each material varies dramatically depending on which steelmaking method you’re using:

| Material | BF-BOF Route (per tonne steel) | EAF Route (per tonne steel) |

|---|---|---|

| Iron ore | 1,370 kg | 586 kg |

| Coal/coke | 780 kg | 150 kg |

| Limestone | 270 kg | 88 kg |

| Scrap steel | 125 kg | 710 kg |

| Electricity | Minimal | 2.3 GJ (~440 kWh) |

The EAF route uses six times more scrap and far less virgin material. That’s why scrap availability heavily influences where EAF plants get built—and why recycled steel is becoming increasingly valuable.

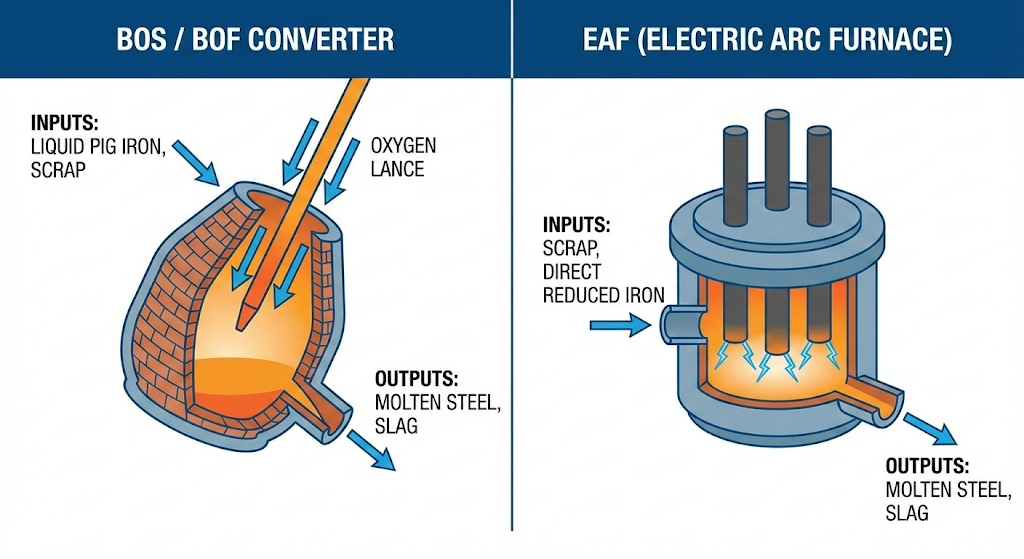

Two production routes dominate the global steel industry: Basic Oxygen Steelmaking (BOS) and Electric Arc Furnace (EAF) steelmaking.

BOS produces about 70% of the world’s steel. The process converts molten pig iron from a blast furnace into steel by blowing pure oxygen through it.

Here’s how it works:

Modern BOF converters handle up to 400 tonnes per heat, with a complete tap-to-tap cycle of around 40 minutes. This method excels at high-volume production of flat products like sheet steel for automotive and construction.

EAF accounts for about 30% of global production—and that share is growing. Instead of starting with iron ore, EAF plants melt recycled scrap steel (or direct reduced iron) using powerful electric arcs.

The process is straightforward:

EAF plants are smaller, cheaper to build, and more flexible than integrated BOS mills. They can be turned on and off as demand changes. That’s why they’re ideal for regional mini-mills and specialty steel production.

| Factor | BOS/BOF | EAF |

|---|---|---|

| Primary input | Iron ore + pig iron | Recycled scrap steel |

| Global share | ~70% | ~30% |

| Capacity per heat | Up to 400 tonnes | 130-180 tonnes |

| CO₂ emissions | 2.2 tonnes per tonne steel | 0.77 tonnes per tonne steel |

| Energy use | 21-23 GJ per tonne | 2-5 GJ per tonne |

| Capital cost | ~$1,100 per tonne capacity | ~$300 per tonne capacity |

| Flexibility | Low (must run continuously) | High (can stop and start) |

The emissions difference is striking. EAF produces roughly one-third the CO₂ of BOS when running on scrap. That’s driving a global shift toward EAF as environmental regulations tighten.

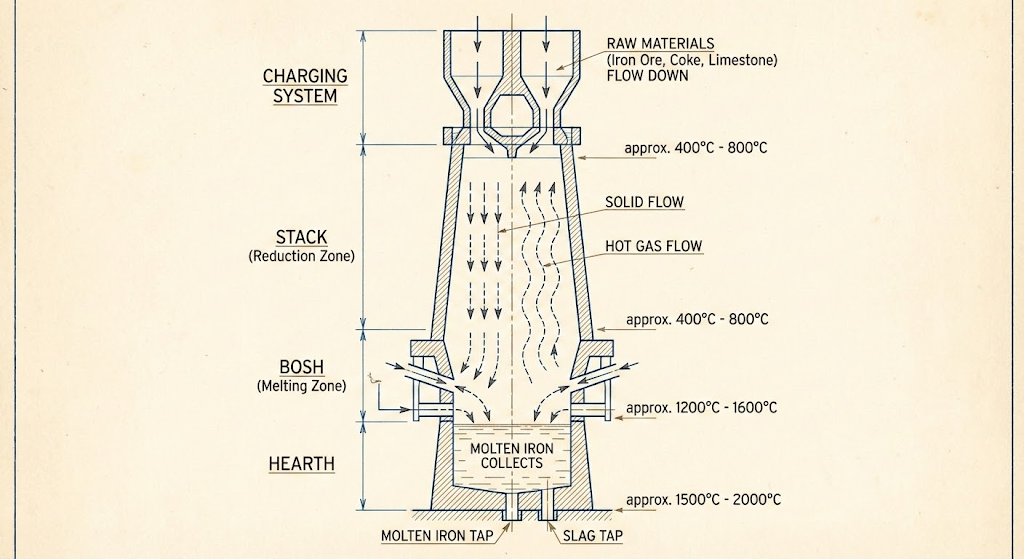

The integrated BF-BOF route transforms iron ore into steel through three main stages.

The blast furnace is where raw iron ore becomes metallic iron. It’s a massive structure—modern furnaces reach 35 meters tall with internal volumes of 4,500 cubic meters.

Iron ore, coke, and limestone are continuously charged from the top. Hot air (called “blast”) enters through pipes at the bottom, reaching temperatures of 1,400-2,100°F. The coke burns, generating carbon monoxide gas that rises through the furnace and strips oxygen from the iron ore.

At 1,200-2,000°C, the iron melts and collects at the bottom. Impurities combine with limestone to form slag, which floats on top. A large blast furnace can produce 10,000 tonnes of molten iron per day.

The output—called pig iron—contains about 4.5% carbon. That’s too brittle for most applications. It needs refining.

The BOF transforms pig iron into steel by removing excess carbon and impurities. Picture a pear-shaped vessel that can tilt to receive the charge and pour out the finished steel.

Molten pig iron and scrap steel are loaded into the converter. Then a water-cooled lance descends and blows pure oxygen at high pressure. The oxygen reacts violently with carbon in the iron, releasing heat and converting carbon to CO₂ gas.

This process is fast—only about 20 minutes of blowing. The temperature rises to over 1,600°C purely from the chemical reactions (no external heat needed). When the target carbon content is reached, the converter tilts and pours the molten steel into a ladle.

Raw steel from the BOF needs fine-tuning before it’s ready for casting. That’s where ladle metallurgy comes in.

The steel sits in a ladle—essentially a giant bucket lined with refractory material. Here, metallurgists perform several critical operations:

Argon gas bubbles through the steel from the bottom, stirring it for uniform temperature and composition. This stage takes 20-60 minutes depending on the steel grade.

The EAF route is simpler and more direct than the integrated BF-BOF process.

Scrap steel arrives at the plant already sorted by grade and composition. An overhead crane loads it into a charge bucket, which then deposits the scrap into the furnace through a retractable roof.

Once loaded, the roof closes and three massive graphite electrodes descend. Electric current—up to 40,000 amps—flows through the electrodes, creating arcs that reach 3,500°C. That’s hot enough to melt the scrap quickly.

The melting cycle takes 40-60 minutes. Some plants preheat the scrap using furnace exhaust gases, which cuts energy consumption by 40-50 kWh per tonne.

Once the scrap is molten, the refining phase begins. Operators add lime and other fluxes to form slag, which absorbs phosphorus and sulfur from the steel.

Oxygen can be injected to remove excess carbon if needed. Then alloying elements go in—chromium for corrosion resistance, manganese for strength, or whatever the specification requires.

Temperature control is critical. Too hot, and you lose alloying elements to oxidation. Too cold, and the steel won’t flow properly for casting.

Like the BF-BOF route, EAF steel goes through ladle treatment before casting. The operations are similar: deoxidation, composition adjustment, degassing if required, and temperature fine-tuning.

For specialty grades like ultra-low carbon steel or high-alloy stainless, additional vacuum treatment removes dissolved gases to extremely low levels.

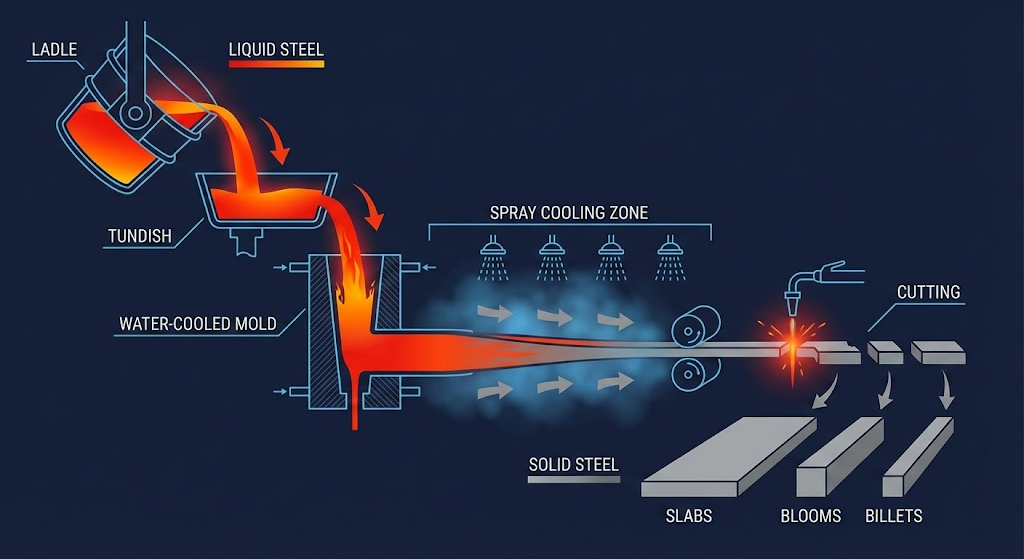

Over 90% of the world’s steel is solidified through continuous casting. It’s far more efficient than the old ingot casting method.

The process works like this:

Continuous casters produce three main shapes: slabs (wide and flat, for sheet products), blooms (square, for structural sections), and billets (smaller squares, for wire and bar).

The key advantage? Continuous casting eliminates the need for primary rolling of ingots, saving energy and improving yield.

The cast shapes aren’t final products—they need forming. Hot rolling is the primary shaping process. Slabs pass through rolling mills at temperatures above 1,000°C, progressively reducing thickness and increasing length.

Secondary forming operations include:

Each step adds value and tailors the steel for specific applications.

Steel production comes down to two main routes: BF-BOF for high-volume commodity production, and EAF for recycling-based and specialty steels.

Both methods share a common finishing process—secondary steelmaking and continuous casting—that determines final quality. Understanding these steps helps you specify the right steel, evaluate suppliers, and make smarter procurement decisions.