One steel foundry tracked their grinding costs and found something startling: 91% of grinding time on a batch of 50 castings was spent removing defects, costing $45,500 annually for that single part type. The problem wasn’t the foundry’s equipment or skill. The problem was how the OEM specified the job.

Most OEMs approach sand casting the way they approach buying commodity parts: get quotes from multiple suppliers, choose the lowest bidder, place the order. This works for fasteners. It fails for castings. The right foundry partner, engaged early and treated as a collaborator rather than a vendor, prevents most first-project failures.

This guide covers what you actually need to know: when sand casting fits your project, how to evaluate foundries, what your RFQ must include, and how to avoid the design mistakes that kill first articles.

Sand casting is the default choice for most industrial metal parts, and for good reason. It handles weight ranges from a few ounces to several tons. It works with nearly every ferrous and non-ferrous alloy. And unlike die casting or investment casting, tooling costs stay manageable for prototype through medium-volume production.

The process excels when you need:

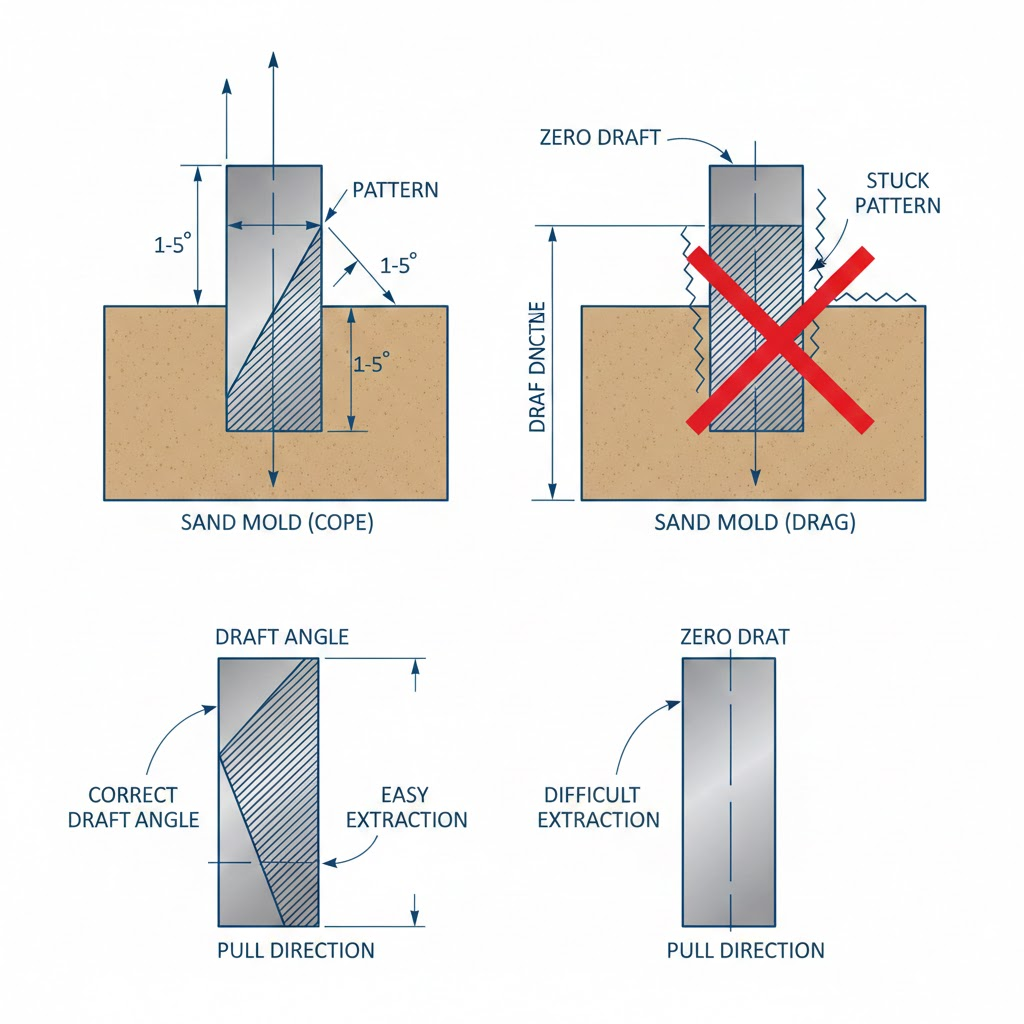

Typical tolerances run +/- 0.125″ (3.2 mm) for general dimensions, with +/- 0.06″ achievable on small to medium castings under 12 inches. Minimum wall thicknesses start at 3 mm for aluminum and light alloys, 5-6 mm for iron and steel. Draft angles of 1-5 degrees are non-negotiable – they’re what allows the pattern to release from the sand.

When does sand casting NOT make sense? If you need tolerances tighter than +/- 0.5 mm, surface finishes better than 125 Ra, or you’re producing 50,000+ identical parts annually. That’s when sand casting vs investment casting comparison becomes critical – investment or die casting may justify their higher tooling costs.

The biggest mistake OEMs make is treating foundry selection like commodity purchasing. You send out an RFQ, collect quotes, pick the lowest bidder. Then you end up with a warehouse full of inexpensive but defective products.

I’ve seen this pattern repeatedly: an OEM selects a foundry based on price, the first articles fail inspection, finger-pointing begins about whether the problem is the design or the casting, and the project burns three months before anyone starts over with a different supplier.

Good foundries operate differently. When State Line Foundries acquired a struggling foundry and transformed their relationship with a pump manufacturer, the OEM reported something they’d never experienced: “For five to six weeks, there wasn’t a single overdue item. I’ve never seen that from a foundry.” That didn’t come from better equipment. It came from treating the relationship as a partnership.

Tim Dorn, VP of Sales and Engineering at Amerequip, describes what that partnership looks like: “It’s true collaboration… it was amazing teamwork. The foundry is there to help us.” Amerequip’s approach includes touring foundries, engaging in direct dialogue about applications, and sharing design concepts early – before drawings are finalized.

Jesse Milks, President of State Line Foundries, puts it bluntly: “The OEM always needs to know the status of any challenges its foundry is facing. There’s no excuse for ineffective communication.”

When evaluating foundries, look beyond certifications and equipment lists:

Bigger isn’t automatically better. Large foundries mean multiple facilities and many clients. Some manage this well; others leave you feeling like another number. Match the foundry’s sweet spot to your project’s actual needs.

Vague specifications don’t just slow down quoting – they inflate costs. Dave Charbauski, a casting industry expert, explains the dynamic: when surface finish requirements are unclear, foundries assume the worst to protect themselves. “Requiring a casting to have high levels of visually defect-free surfaces can easily add 15% or more to the cost.”

Most RFQs fail because they focus on what the OEM wants rather than what the foundry needs to quote accurately. A complete casting RFQ includes:

Technical documentation:

Material specification:

Quantity and volume:

Surface and tolerance requirements:

Secondary processing:

Application context:

The foundry and OEM need to develop shared inspection criteria so both understand what is and is not acceptable. This conversation should happen before production begins, not when the first batch fails incoming inspection.

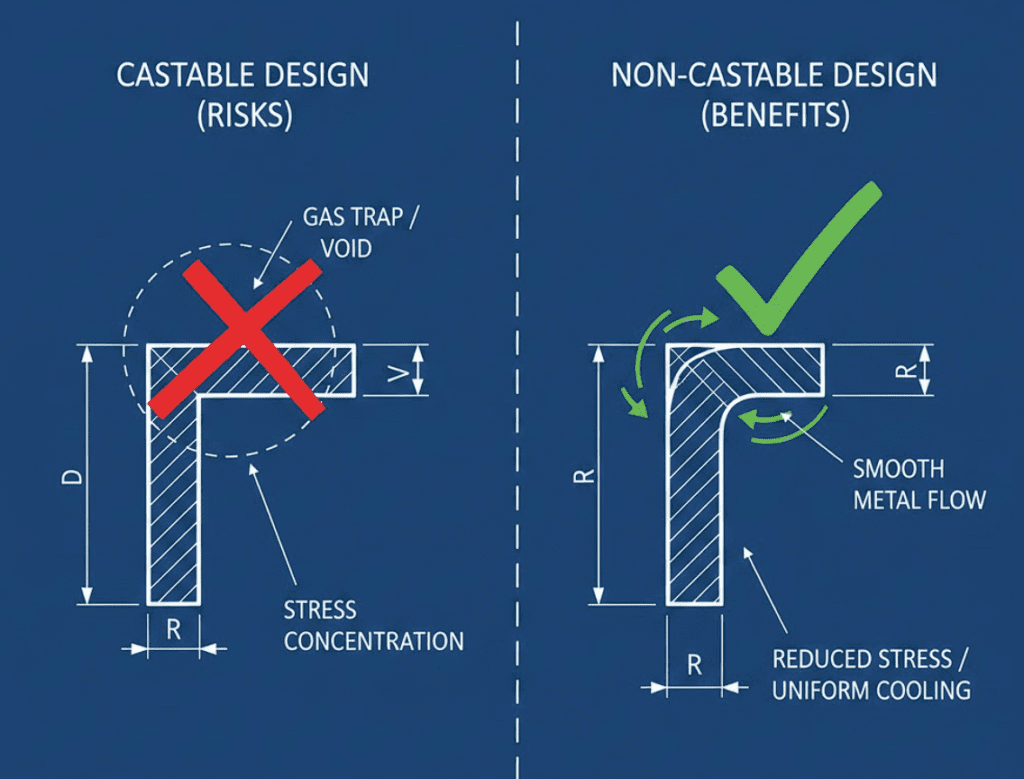

Design decisions determine 70-80% of manufacturing cost – but only 8% of the product budget is spent by the time design is locked. Early DFM collaboration prevents the most expensive rework.

Before sending drawings to a foundry, ask yourself:

The most effective approach treats your foundry as a design partner. When ABC Castings was struggling with quality issues, their customer didn’t switch suppliers. Instead, they sent quality experts to work directly with the foundry on improving processes. They got better castings and a more capable foundry.

This collaboration works both ways. A good foundry will push back on designs that cause problems. If your foundry’s answer to every issue is the same solution – “add more chills” or “increase the riser” – that’s a warning sign. Real engineering means diagnosing root causes.

Getting sand casting right the first time comes down to three actions:

Your first project’s success depends on choosing a partner, not a vendor. The lowest quote rarely delivers the lowest total cost.