A Class 300 valve does not handle 300 PSI. That number refers to ASME B16.34 pressure-temperature rating tables, not actual working pressure. A Class 300 carbon steel valve handles approximately 740 PSI at ambient temperature but only 450 PSI at 400C. Get the relationship wrong between pressure class, material, and temperature, and you specify valves that fail under operating conditions.

This guide covers the ASTM material standards, pressure-temperature ratings, and sand casting considerations you need to specify valve body castings correctly.

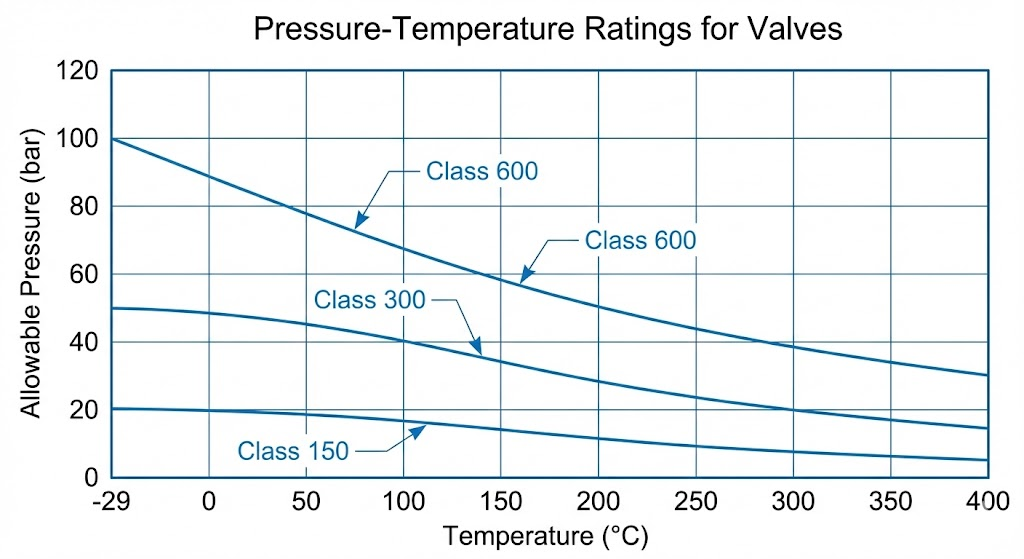

Pressure class designations (150, 300, 600, 900, 1500, 2500) indicate pressure-temperature rating groups per ASME B16.34, not direct PSI values. The allowable working pressure decreases as temperature increases because material strength deteriorates with heat.

For Group 1.1 materials (carbon steel WCB), the pressure-temperature relationship looks like this:

| Pressure Class | -29 to 38C | 100C | 200C |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class 150 | 19.6 bar (285 psi) | 17.7 bar | 13.8 bar |

| Class 300 | 51.1 bar (740 psi) | 46.6 bar | 43.8 bar |

| Class 600 | 102.1 bar (1480 psi) | 93.2 bar | 87.6 bar |

Never assume the class number equals your working pressure. Before specifying a pressure class, check the P-T rating table for your specific material group at your maximum operating temperature. A Class 150 valve rated for 285 psi at ambient drops to 200 psi at 200C.

Material selection depends on operating temperature, pressure requirements, and the corrosiveness of the flow media. Four ASTM specifications cover most sand cast valve body applications.

WCB is the most widely used valve body material for non-corrosive service. It handles temperatures from -29C to 425C and offers good weldability for field repairs.

Mechanical Properties:

WCB costs less than stainless alternatives and provides adequate performance for water, steam, oil, and gas in moderate conditions. For most industrial valve applications where corrosion is not a primary concern, WCB is the default choice.

CF8M is the cast equivalent of 316 stainless steel, offering enhanced corrosion resistance due to its molybdenum content. Temperature range extends from -268C to 649C.

Mechanical Properties:

CF8M costs more upfront, but it often outlasts carbon steel in corrosive or marine environments. Specify CF8M when handling acids, chlorides, or seawater where WCB would corrode within months. Different stainless steel grades suit different corrosive media.

LCB is designed for cryogenic and low-temperature applications where standard carbon steel becomes brittle. It handles temperatures down to -46C (-50F).

Impact Test Requirements:

Specify LCB for LNG, cryogenic storage, or any application below -29C where WCB’s impact toughness is insufficient.

Ductile iron offers a cost-effective alternative to steel for lower-pressure applications. Grade 70-50-05 (equivalent to GGG-50) provides good strength with some ductility.

Mechanical Properties:

The difference between gray iron and ductile iron lies in graphite structure: ductile iron’s spheroidal nodules provide impact resistance that gray iron lacks. For water distribution valves and lower-pressure industrial applications, ductile iron delivers adequate performance at roughly 60% of steel’s cost.

Valve bodies present specific challenges for sand casting: complex internal passages, variable wall thicknesses, and pressure-integrity requirements. The pattern and mold design directly affect casting quality.

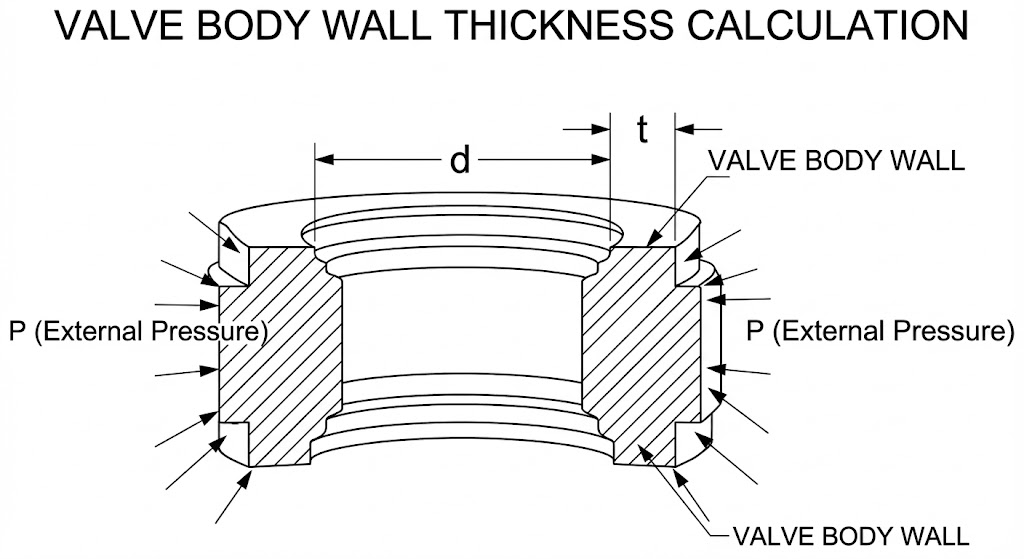

Minimum wall thickness for sand castings is typically 0.150 inches (3.8 mm), but valve bodies require additional thickness for pressure containment. API 600 specifies heavier walls than ASME B16.34 for the same pressure rating.

For valves exceeding ASME B16.34 size limits (currently 24 inches for most classes), MSS SP-67 provides a calculation method:

t = (1.5 P d) / (2S – 1.2P)

Where:

For a 60-inch carbon steel check valve, extrapolating ASME B16.34 wall thicknesses creates unnecessary weight and cost. The MSS formula matches material to actual stress requirements.

Different materials shrink differently during solidification. Pattern makers must account for this shrinkage to achieve final dimensions.

| Material | Shrinkage Allowance |

|---|---|

| Gray cast iron | 0.55-1.00% |

| Carbon steel | 1.5-2.0% |

| Manganese steel | 2.60% |

| Stainless steel | 2.0-2.5% |

Before designing the pattern, consider that a 24-inch valve body in carbon steel shrinks approximately 0.36-0.48 inches. Underestimating shrinkage means undersized castings that cannot be salvaged.

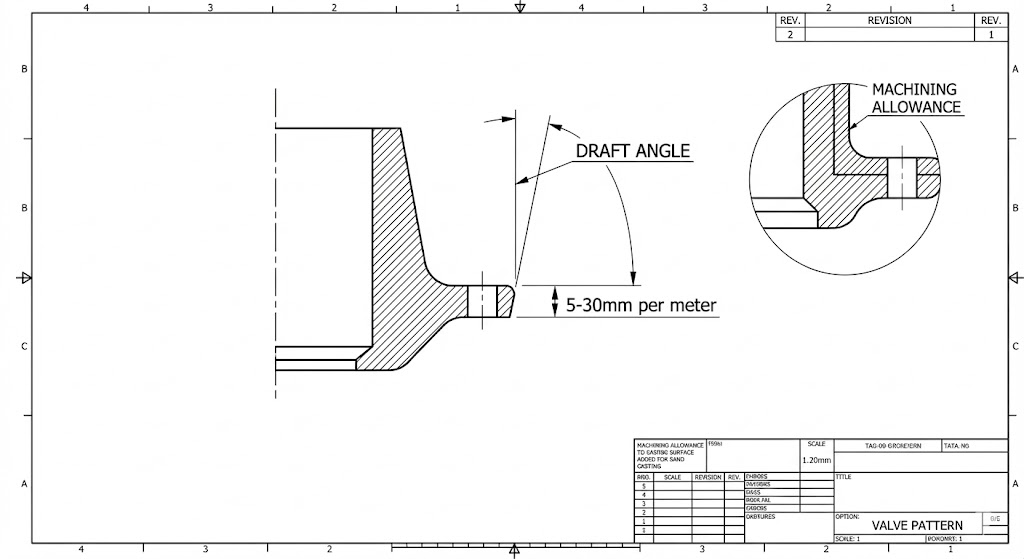

Draft angles allow pattern withdrawal from the mold. Standard practice calls for 5-30 mm per meter on vertical surfaces, depending on pattern depth and complexity.

Machining allowance of 2-15 mm must be added to surfaces requiring post-casting machining. Valve body flanges and seating surfaces typically need the full allowance; non-critical surfaces can use less.

The sand casting process fundamentally differs from die casting or investment casting in these allowances. Sand casting’s coarser tolerances require more machining stock than precision processes.

Valve body castings require testing to verify pressure integrity and material properties. The extent of testing depends on application criticality and specification requirements.

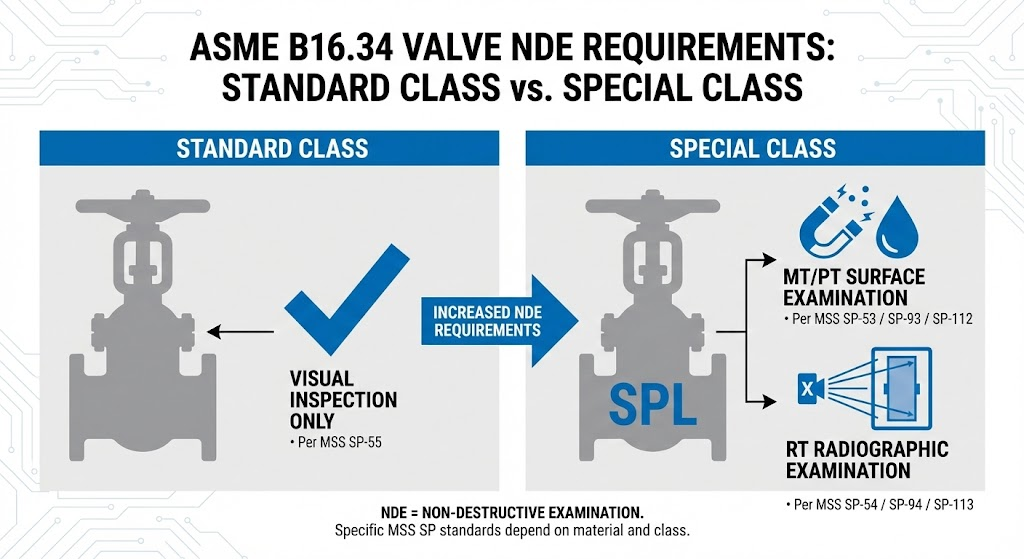

ASME B16.34 defines two examination classes:

Standard Class: No mandatory NDE on cast valve bodies. Acceptable for general industrial service where consequences of failure are manageable.

Special Class (SPL marking): Requires surface examination (MT or PT) plus radiographic examination of critical areas per Section 8. Special Class valves can achieve higher pressure ratings at the same temperatures.

For critical service or high-consequence applications, specify Special Class. The additional NDE cost is minor compared to field failure costs.

Standard hydrostatic testing pressures the valve body at 1.5x design pressure for at least 10 minutes. This test verifies gross leakage but has limitations.

One manufacturer found that valves passed hydrostatic testing but showed classic shrinkage porosity after painting. Visual defects appearing after surface preparation can indicate subsurface issues that water-based testing missed.

Low-pressure pneumatic testing (5-7 bar with soap solution) catches micro-porosity that water-based tests can mask. One valve manufacturer implemented air testing before hydrostatic testing and caught approximately five extra valves per month with micro-porosity that would have reached customers.

For bronze or stainless valve bodies where micro-porosity is more common, adding pneumatic testing to the inspection sequence cuts field failures measurably.

A complete valve body specification includes more than just material and pressure class. Missing information leads to rejected castings or endless negotiation over acceptance criteria.

Essential specification elements:

Include repair acceptance criteria upfront. Without clear thresholds, foundries and buyers argue endlessly about whether a defect is cosmetic or structural. Defining these limits in the purchase order prevents disputes.

Foundries with valve casting capabilities should provide sample MTRs and reference parts from similar projects. Ask about their experience with your specific material grade and pressure class combination.

Material selection follows service conditions: temperature range determines whether you need WCB, LCB, or CF8M; corrosiveness of the flow media determines whether stainless grades are justified. Pressure class selection requires checking P-T tables at your maximum operating temperature, not assuming the class number equals PSI.

The specification elements listed above form your RFQ checklist. Start with material and pressure class, then work through NDE requirements, testing, and repair acceptance criteria. Complete specifications get accurate quotes; incomplete specifications get change orders.

For critical valve applications, consider Special Class NDE and pneumatic porosity testing even if not explicitly required by your end user. The incremental cost is small compared to field failure investigation and replacement.