Test bars lie. Not intentionally, but the numbers on your material certificate come from a standardized sample that cooled at a rate your actual casting probably never experienced. Foundry engineers confirm that results from test coupons are typically 10-20% higher than properties measured in actual castings. The larger your casting’s cross section, the larger that gap becomes.

This disconnect explains why specifying ASTM A48 Class 40 does not guarantee Class 40 performance in your finished part. Section thickness, cooling rates, and application requirements often matter more than the grade number printed on a certificate. Here is how to select gray iron grades with these realities in mind.

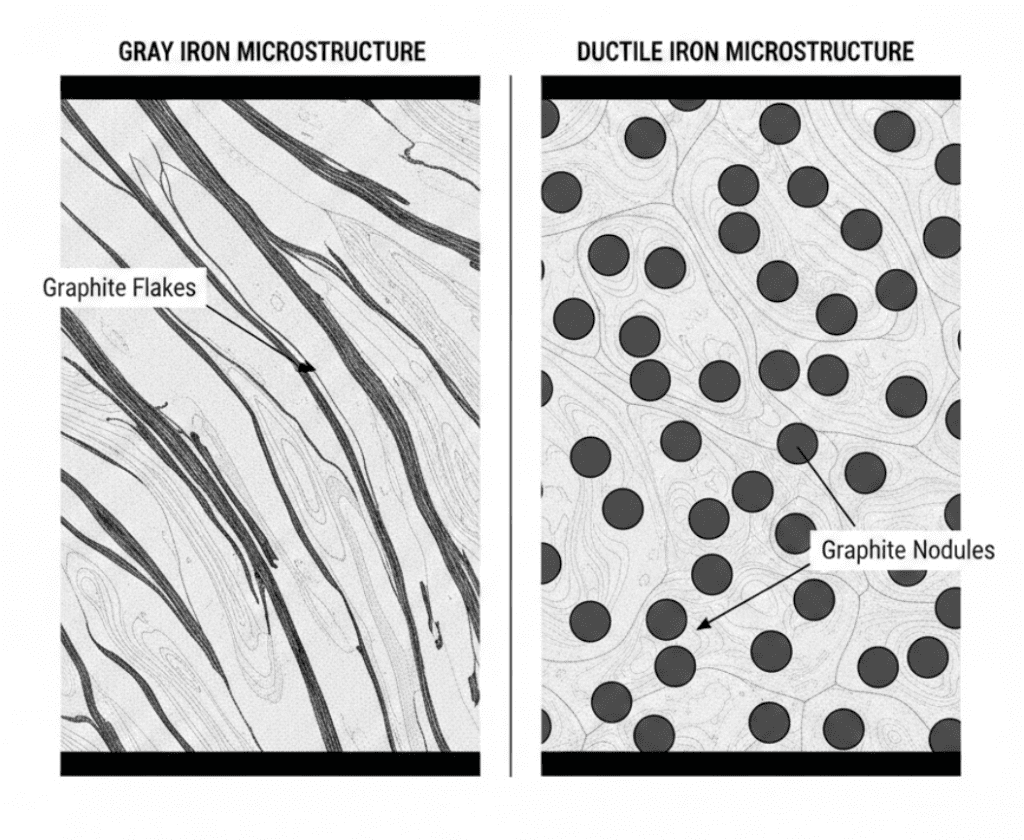

Gray iron gets its name from the gray fracture surface created by graphite flakes distributed throughout the iron matrix. These flakes act as natural stress concentrators, making gray iron more brittle than ductile iron with its spherical graphite nodules. But this apparent weakness delivers real advantages.

The graphite flakes interrupt vibration transmission, giving gray iron roughly double the damping capacity of ductile iron. For machine tool beds, engine blocks, and pump housings where vibration control matters, this property outweighs tensile strength limitations. The flakes also act as chip breakers during machining, making gray iron one of the easiest cast metals to machine.

Gray iron tensile strength ranges from 150-400 MPa, compared to 400-700 MPa for ductile iron. Elongation stays below 1% versus 10-18% for ductile iron. These numbers make the choice clear: if your application involves impact loading, significant bending stress, or needs ductility as a safety margin, gray iron is the wrong material. But for static loads with vibration concerns, gray iron often outperforms more expensive alternatives.

From a sourcing perspective, gray iron castings cost 15-25% less than comparable ductile iron parts. The total cost advantage can be even larger when you factor in faster machining rates and reduced tool wear.

ASTM A48 classifies gray iron by minimum tensile strength. A Class 30 casting must achieve at least 30,000 psi (207 MPa) tensile strength when tested per the standard. The classification seems straightforward, but the standard includes a critical detail that most specifications overlook.

The tensile strength measured in separately cast test bars is intended to provide consistency between production lots and foundries. It is not intended to represent the tensile strength in the actual casting. This language appears directly in the ASTM A48 standard. The test bar measures melt quality, not part performance.

Class 20 through Class 35 grades dominate general industrial applications. These grades have higher carbon equivalents, producing larger graphite flakes that maximize damping and machinability.

Class 20 (minimum 20 ksi / 138 MPa) works well for covers, housings, and non-structural components where machinability matters more than strength. Class 25 and Class 30 handle moderate loads while maintaining excellent machinability. Class 35 (minimum 35 ksi / 241 MPa) represents the practical upper limit before damping capacity drops significantly.

For sand casting applications where vibration control or thermal conductivity matters, these grades typically outperform higher-strength options.

Class 40 through Class 60 grades achieve higher strength through lower carbon equivalents and tighter process control. Class 40 (minimum 40 ksi / 276 MPa) is commonly specified for gears, cylinder liners, and structural brackets. Class 50 and Class 60 push tensile strength to 50-60 ksi (345-414 MPa) but require careful foundry practice.

Higher grades mean higher hardness, higher price, and higher production difficulty. An unnecessary increase in strength and hardness increases casting cost while also increasing machining cost through lower cutting speeds and faster tool wear. Specify the grade your application actually needs, not the highest grade the foundry can produce.

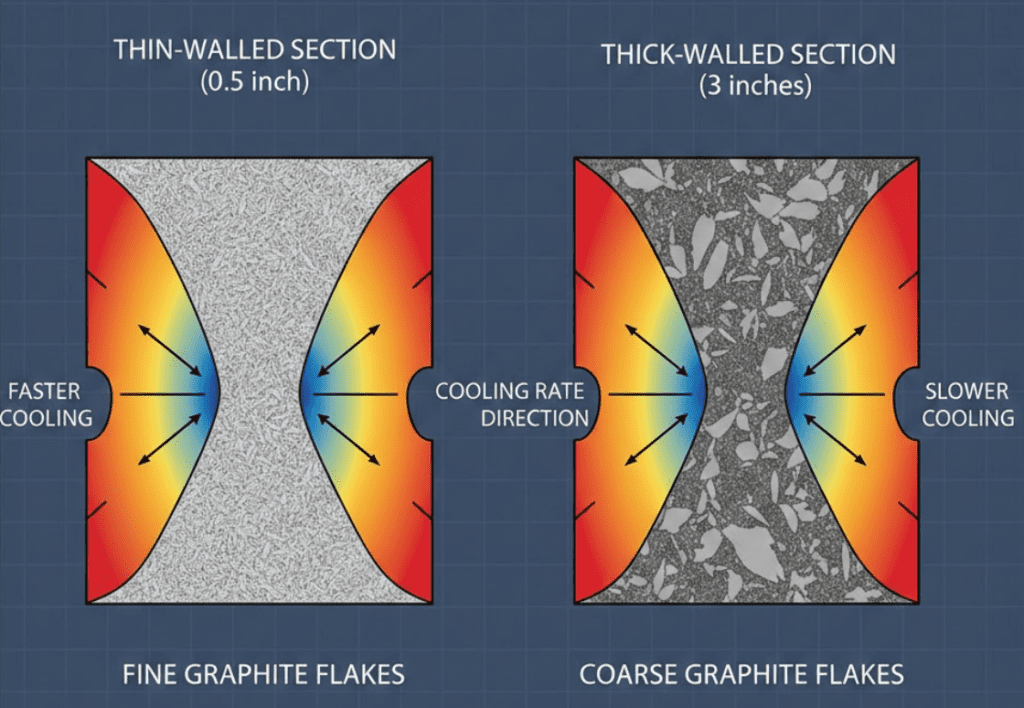

Gray iron properties depend on graphite flake size, and flake size depends on cooling rate. Thin sections cool rapidly, producing fine graphite flakes and higher properties. Thick sections cool slowly, growing coarse flakes that reduce strength and hardness.

This section sensitivity creates a fundamental mismatch between test bar data and actual casting performance. A 1-inch diameter test bar cools at a specific rate. Your 3-inch wall section cools much more slowly. The properties in that thick section will fall below the test bar values, sometimes significantly.

Research on section thickness effects confirms this relationship: thin sections contain small graphite flakes with higher hardness, while thick sections develop larger flakes with correspondingly lower properties. The test bar does not predict this variation.

The practical consequence becomes severe when specifying higher grades in thin sections. Class 40 and above have lower carbon equivalents that make them susceptible to chilling in thin sections. Rapid cooling in thin walls can produce hard, brittle carbides instead of graphite, making the casting unmachineable without heat treatment. Annealing removes the carbides but typically drops properties by one grade level, turning your Class 40 specification into Class 30 performance.

I have seen procurement teams insist on Class 40 for thin-walled housings, then reject castings for excessive hardness. The foundry followed the specification correctly. The specification was wrong for the geometry.

Starting with application requirements rather than grade numbers produces better outcomes. What does your casting actually need to do?

Machine tool beds, engine blocks, compressor bases, and pump housings benefit from gray iron’s damping capacity. Lower grades with larger graphite flakes provide the best vibration absorption. Class 25 through Class 35 typically delivers optimal damping performance while meeting structural requirements.

Specifying Class 40 or higher for these applications sacrifices the property you actually need. The machine tool industry deliberately selects lower-strength gray iron because damping matters more than tensile strength for precision equipment.

Brackets, supports, and components under sustained load may justify higher grades. But consider your actual section thicknesses. A Class 40 specification for a casting with 2-inch thick walls may deliver Class 35 or lower properties in those thick sections regardless of what the test bar shows.

For critical structural applications, consider requesting test specimens cut from actual castings rather than separately cast bars. Some standards, like Norwegian Norsok specifications, now require test block thickness to match actual component sections.

The brake rotor industry demonstrates that higher strength grades can be the wrong choice. Automotive rotors experience extreme thermal cycling that tests thermal conductivity and crack resistance more than tensile strength.

Rotor manufacturers deliberately use lower-strength, higher-carbon gray iron because thermal conductivity correlates with carbon content and graphite size. High-carbon grades with 150-200 MPa tensile strength outperform Class 250 (G3000) rotors in thermal performance. When one manufacturer tested high-carbon material against standard G3000, the high-carbon version demonstrated 100% better noise suppression and superior thermal behavior.

The lesson extends beyond rotors: match the grade to your actual performance requirements, which may favor lower strength classes.

Effective gray iron specifications start with application analysis, not grade selection. Define what the casting must do, consider the section thicknesses involved, then select a grade that delivers required performance without over-specification.

For castings with varying section thicknesses, specify properties at critical locations rather than relying on separately cast test bars. Request test specimens from representative sections when feasible. For thin-walled higher-grade castings, discuss chilling risk with your foundry and confirm their process handles your geometry.

Avoid the common mistake of specifying the highest grade you think the application might need. Over-specification increases casting cost, machining cost, and defect risk without improving actual performance. A Class 35 casting that meets your functional requirements costs less and machines faster than a Class 40 that exceeds them.

Gray iron grade selection works best when you think beyond the class number. Consider your actual section thicknesses and cooling rates. Match the grade to application requirements, not maximum available strength. Verify that test bar data correlates to your critical casting sections.

For most industrial applications, Class 25 through Class 35 delivers the best balance of properties, cost, and manufacturability. Reserve Class 40 and above for applications where section geometry supports higher grades and where the strength increase justifies added cost and complexity. The grade number on your material certificate matters less than whether the casting performs in service.