Steel foundries average just 53% casting yield—nearly half of the metal poured becomes scrap, gates, or risers. That figure, from an American Foundry Society survey of 93 foundries, shows what can happen when you don’t account for sand casting limitations before committing to a project.

Sand casting remains the most accessible metal forming process for prototypes and low-volume production. But its inherent constraints in surface finish, dimensional tolerance, and defect susceptibility can drive up total costs if you specify it for the wrong application. Here’s where sand casting falls short—and the specific thresholds that signal when alternatives make better economic sense.

Sand casting produces the roughest surfaces of any common casting method, typically ranging from Ra 12.5-25 micrometers (200-500 RMS). Investment casting, by comparison, achieves Ra 0.8-2.0 micrometers. Die casting sits between them at Ra 0.5-1.5 micrometers.

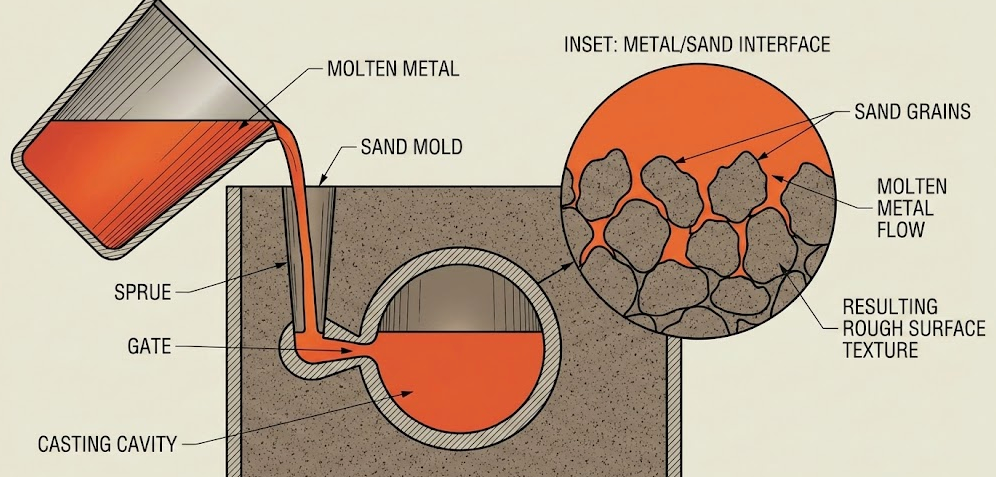

The roughness stems from physics, not process control. Molten metal flows into the spaces between sand grains, creating what industry sources describe as “peaks and valleys” on the casting surface. Larger grains produce larger peaks. You might assume finer sand solves this problem, but there’s a trade-off: finer grains pack more closely, reducing mold permeability. Gases that would escape through coarse sand get trapped, increasing porosity risk.

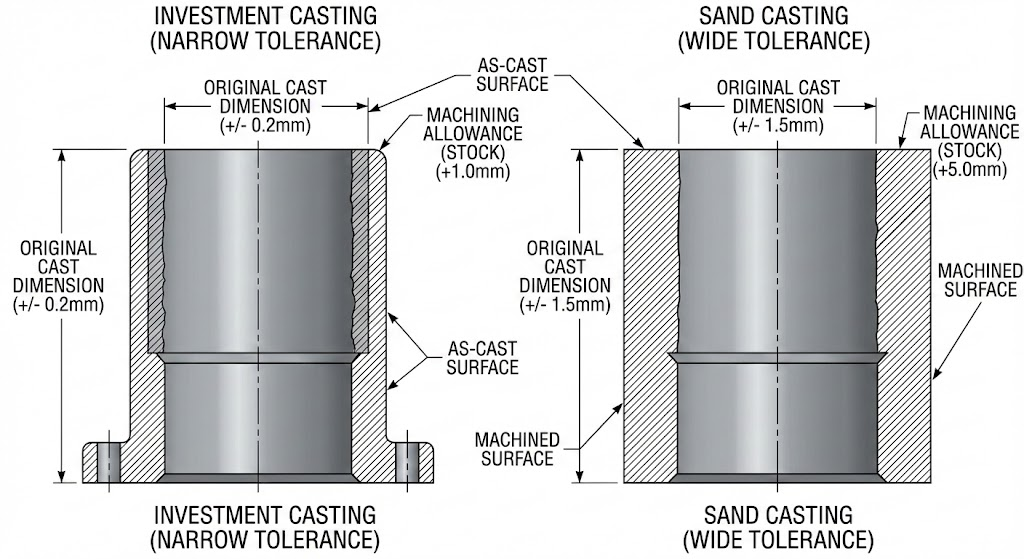

From a sourcing perspective, this surface limitation cascades into machining costs. Sand castings typically require 2-5 mm machining allowance versus 0.5-1.5 mm for investment castings. If your part has multiple machined surfaces, that extra material removal adds significant time and cost. For parts where the as-cast surface is acceptable—pump housings, machine bases, counterweights—this limitation doesn’t matter. For parts requiring smooth mating surfaces or aesthetic finish, factor machining into your total cost calculation.

Sand casting tolerances follow ISO 8062-3, which specifies DCTG (Dimensional Casting Tolerance Grade) ratings. Production iron castings typically fall within DCTG 8-12, while short-run or single castings may only achieve DCTG 11-15.

To translate those grades into practical numbers: a foundry like LB Foundry specifies tolerances of +/-0.030 inches (0.76 mm) for the first 6 inches, adding 0.003 inches per inch beyond that. Investment casting holds roughly half that variation: +/-0.010 inches for the first inch, then +/-0.003-0.005 inches per additional inch.

These numbers matter when you calculate machining stock. Wider tolerance bands require larger machining allowances to guarantee final dimensions. A part with ten critical dimensions, each requiring extra stock for sand casting variance, accumulates cost quickly.

The tolerance also determines what you can cast versus what you must machine. Cast-in holes, threads, and fine features often become impractical at sand casting tolerances. An engineer on Eng-Tips noted that switching from investment casting to sand casting forced them to drill holes that were previously cast-in—fine details like numbers and letters lost definition entirely.

Porosity and shrinkage defects are inherent to sand casting. Gas porosity occurs when gases trapped in the molten metal or released from the mold during solidification form voids. Shrinkage porosity develops when molten metal contracts during cooling without sufficient feed metal available.

Industry benchmarks suggest iron foundries targeting automotive work aim for 5% or less scrap rate. Management typically initiates improvement projects when scrap exceeds 3%. For complex castings that push process limits, some foundries accept 10% scrap with customer agreement, building that loss into pricing.

The hidden cost lies in rework, not just scrap. According to Modern Casting magazine, 91% of grinding time on an order for 50 1,000-lb steel castings was spent grinding defects—not gates, risers, or parting lines, but defects. That’s labor cost embedded in every acceptable casting that doesn’t appear on the scrap report.

If you’re specifying complex geometries with thin walls or deep pockets, expect higher defect rates and build contingency into your cost model.

Sand casting imposes geometric limits that affect both cost and feasibility.

Minimum wall thickness runs approximately 0.150 inches (3.8 mm) for steel, varying by alloy: aluminum at 0.10 inches, magnesium at 0.13 inches. Thinner walls create fill problems and excessive cooling stresses.

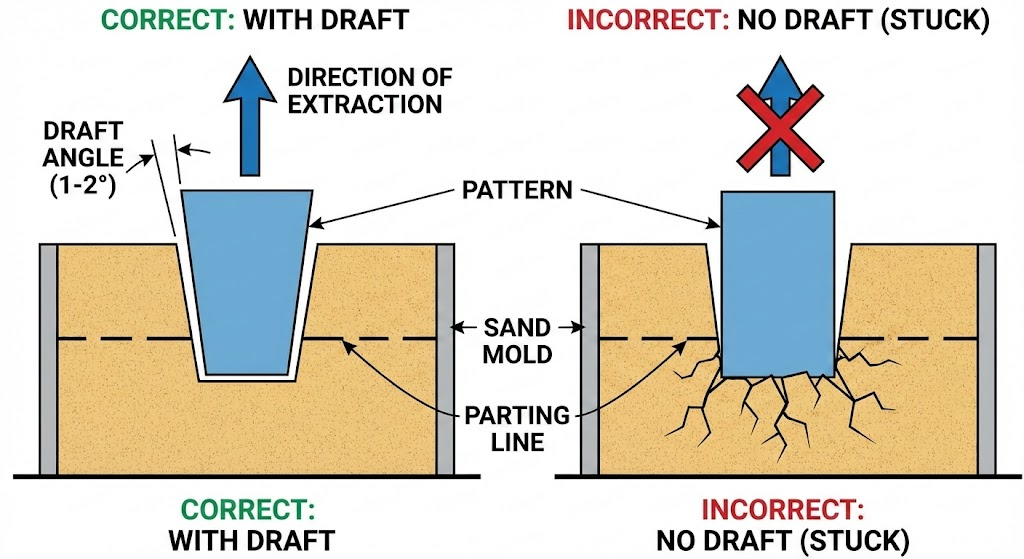

Draft angles—the taper allowing pattern removal from the mold—require a minimum of 1 degree, with 2 degrees standard. Anything more vertical than 1 degree risks pattern damage during extraction. One forum practitioner warned that switching from investment to sand casting required “substantially increased” draft angles, fundamentally changing part geometry.

Parting lines leave witness marks requiring cleanup. Undercuts require cores, adding cost and potential dimensional variation. Cast-in features like ribs, bosses, and holes need generous fillets and radii—sharp internal corners create stress concentrations and fill problems.

The total cost of ownership includes qualification costs. If you’re transitioning an existing part from investment to sand casting, anticipate rework cycles as patterns and process parameters dial in.

The decision framework hinges on three factors: tolerance requirements, production volume, and surface finish needs.

Choose investment casting when tolerances must be tighter than +/-0.5 mm, surfaces require Ra below 6.3 micrometers, or part geometry includes thin walls, fine detail, or minimal draft. Volume sweet spot runs from approximately 100 to 10,000 units—enough to justify pattern tooling but not enough for permanent die investment.

Investment casting tooling costs more upfront, but near-net-shape production often eliminates machining entirely. An investment casting may cost more per piece, yet when calculating the secondary costs of sand casting—machining, grinding, higher scrap—the total cost may wash out or favor investment.

Die casting becomes economical above 1,000-10,000 units depending on complexity, with clear advantage above 10,000 pieces. It suits aluminum, zinc, and magnesium alloys but not ferrous metals. Tooling costs $20,000-$100,000+ versus $500-$5,000 for sand casting patterns.

Consider die casting when parts require consistent high volume, tight tolerances (CT1-CT4), and excellent surface finish (Ra 0.5-1.5 micrometers). If your annual volume exceeds 10,000 identical parts in suitable alloys, die casting typically delivers lowest total cost.

Process selection impacts total cost more than unit price. A sand casting that requires extensive machining, accepts higher scrap rates, and demands design compromises may cost more than an investment casting that arrives near-net-shape.

Before committing to sand casting, verify that your tolerance requirements fall within DCTG 8-12, surface finish needs accommodate Ra 12.5-25 micrometers, and production volume stays below 1,000 units. If any of those parameters pushes toward investment or die casting territory, run a total cost analysis including machining, scrap allowance, and qualification costs. The cheapest pattern doesn’t always produce the cheapest part.