Choosing between gray iron and ductile iron trips up even experienced engineers. Both materials belong to the cast iron family, but they behave completely differently under stress. Pick the wrong one, and you’re looking at cracked components, premature failures, or unnecessarily expensive parts.

Here’s the thing: the confusion starts with terminology. When someone says “cast iron,” they usually mean gray iron. When they say “ductile iron,” they’re talking about a specific type of cast iron with nodular graphite. Same family, different materials, vastly different properties.

I’ve seen engineers default to ductile iron “just to be safe” when gray iron would work perfectly fine at half the cost. I’ve also seen gray iron specified for pressure applications where it had no business being used. Both mistakes cost money and time.

Cast iron is any iron-carbon alloy containing more than 2% carbon. That’s the technical definition that separates it from steel.

The cast iron family has four main members: gray iron, white iron, ductile iron, and malleable iron. Each one has different graphite structures and properties. But in everyday engineering discussions, “cast iron” almost always means gray iron. It’s the most widely used cast material by weight.

The chemical makeup of these materials looks similar on paper, but one small difference changes everything.

| Element | Gray Iron | Ductile Iron |

|---|---|---|

| Carbon | 2.5-4% | 3-4% |

| Silicon | 1-3% | 1.8-2.8% |

| Magnesium | None | 0.04-0.06% |

| Sulfur | Up to 0.15% | Must be <0.02% |

That tiny amount of magnesium is the game-changer. It transforms the graphite structure from flakes to spheres. The sulfur content matters because too much sulfur interferes with the magnesium treatment. Foundries have to keep base iron sulfur below 0.02% for successful nodularization.

Silicon plays a supporting role by reducing carbon solubility in the matrix, which encourages graphite formation. But magnesium does the heavy lifting when it comes to creating ductile iron’s unique properties.

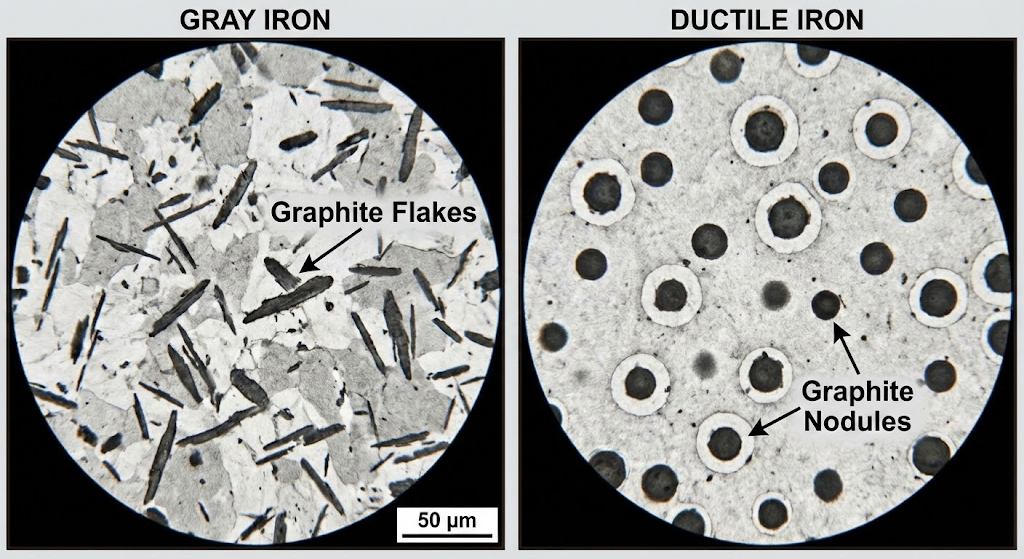

Look at gray iron under a microscope, and you’ll see graphite flakes scattered randomly throughout the metal matrix. These flakes look like tiny black lines running through the material.

Here’s why this matters: those flakes act as stress concentrators. When you apply tension to gray iron, stress builds up at the tips of those graphite flakes. The material fractures before it can bend or stretch. This is why gray iron has essentially zero ductility.

The upside? Those same flakes interrupt sound and vibration waves traveling through the material. Gray iron absorbs vibrations that would ring through steel or ductile iron. That’s why engine blocks and machine tool bases love gray iron.

Break a piece of gray iron, and the fracture surface looks gray. That’s where the name comes from. You’re seeing the exposed graphite flakes at the break point.

Ductile iron’s graphite forms as spherical nodules instead of flakes. Under the microscope, they look like tiny balls scattered throughout the matrix.

The typical microstructure shows a “bull’s-eye” pattern: a graphite nodule in the center, surrounded by a ring of ferrite, which is then surrounded by pearlite. The exact ratio of ferrite to pearlite depends on cooling rate and heat treatment, and it directly affects the mechanical properties.

Why do nodules make such a difference? Think about stress concentration. A sharp crack tip multiplies stress dramatically. A sphere doesn’t. When stress hits a graphite nodule, it distributes around the sphere rather than concentrating at a point.

This means ductile iron can actually stretch before it breaks. It can absorb impact energy by deforming plastically. It behaves more like steel than like traditional cast iron.

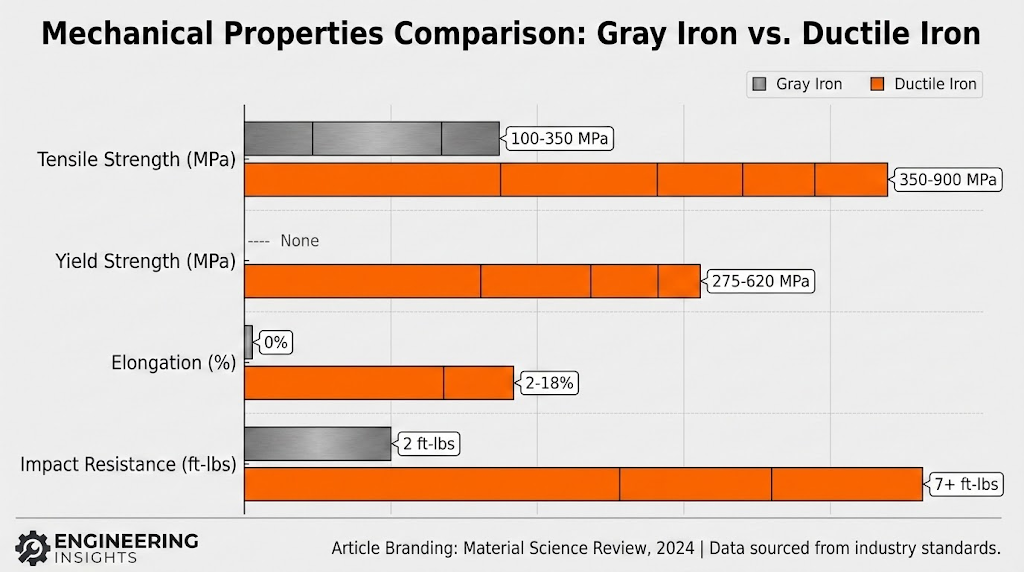

The numbers tell the real story. Here’s a comprehensive comparison:

| Property | Gray Iron | Ductile Iron |

|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | 100-350 MPa | 350-900 MPa |

| Yield Strength | No measurable yield | 275-620 MPa |

| Elongation | 0% | 2-18% |

| Impact Resistance | ~2 ft-lbs | 7+ ft-lbs |

| Hardness (HB) | 180-300 | 170-280 |

| Thermal Conductivity | 46 W/m·K | 36 W/m·K |

| Damping Capacity | Excellent | Good |

Ductile iron’s tensile strength ranges from 350 to 900 MPa depending on grade and heat treatment. That’s two to three times stronger than gray iron’s 100-350 MPa range. Austempered ductile iron (ADI) pushes past 1000 MPa.

The yield strength difference is even more dramatic. Gray iron doesn’t have a measurable yield strength because it fails by brittle fracture. There’s no plastic deformation before failure. You can’t design around a yield point that doesn’t exist.

Ductile iron yields at 275-620 MPa depending on grade. ASTM A536 60-40-18 grade yields at 276 MPa minimum. Grade 65-45-12 hits around 450 MPa. This gives you a real safety margin in design calculations.

Gray iron has zero measurable elongation. Pull on a tensile test specimen, and it snaps without stretching.

Ductile iron elongates 2-18% before failure. The ferritic grade A395 stretches 18-30% in some cases. That’s steel-like behavior from a cast material.

Impact resistance shows an even starker contrast. Gray iron handles about 2 foot-pounds in a Charpy test. Ductile iron’s minimum spec requires 7 foot-pounds. Some grades exceed 15 foot-pounds.

What does this mean practically? A gray iron pipe that gets hit by an excavator bucket cracks and shatters. A ductile iron pipe dents and deforms but keeps working. That’s the difference between a repair and a catastrophic failure.

Gray iron isn’t inferior across the board. It genuinely outperforms ductile iron in several areas.

Vibration damping is the big one. Gray iron’s damping capacity is significantly better than ductile iron, which itself has 6.6 times more damping than SAE 1018 steel. For machine tool bases and engine blocks, this damping prevents chatter and extends tool life.

Thermal conductivity runs 46 W/m·K for gray iron versus 36 W/m·K for ductile iron. That 25% advantage matters for brake rotors, cookware, and any application where heat dissipation is critical.

Machinability is roughly 20% better in gray iron. The graphite flakes act as chip breakers and provide lubrication. Feeds and speeds can run higher, and tool life improves. For high-volume production, this translates directly to cost savings.

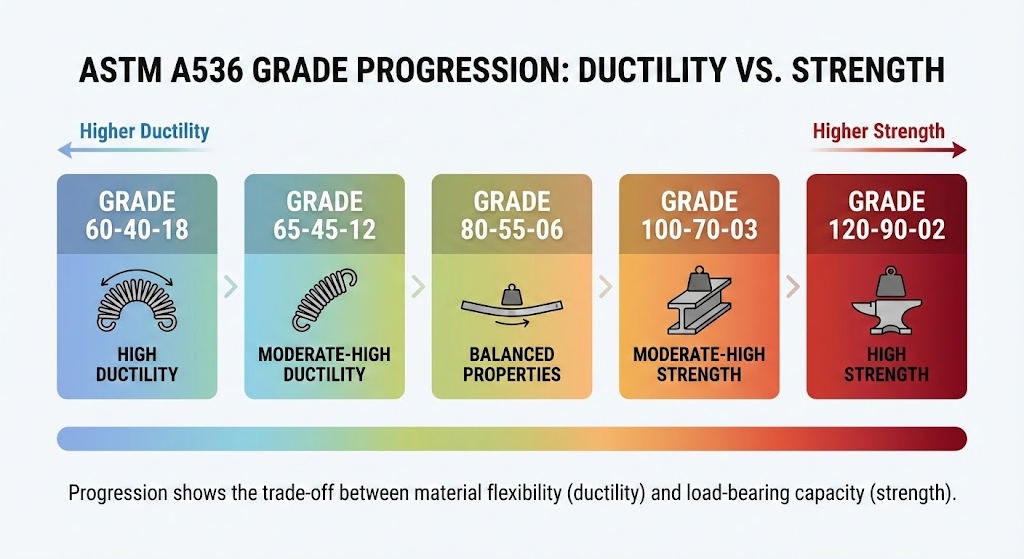

ASTM A536 is the primary specification for ductile iron castings. The grade naming convention tells you everything: Tensile Strength – Yield Strength – Elongation, all in ksi.

| Grade | Tensile (ksi) | Yield (ksi) | Elongation (%) | Typical Heat Treatment |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 60-40-18 | 60 | 40 | 18 | Full ferritizing anneal |

| 65-45-12 | 65 | 45 | 12 | As-cast or heat treated |

| 80-55-06 | 80 | 55 | 6 | As-cast or heat treated |

| 100-70-03 | 100 | 70 | 3 | Quench and temper |

| 120-90-02 | 120 | 90 | 2 | Quench and temper |

Grade 60-40-18 maximizes ductility with a fully ferritic structure. It’s the go-to for impact-resistant applications. Grade 65-45-12 balances strength and ductility for general-purpose use. The higher grades sacrifice elongation for increased strength.

The first number (tensile strength) increases as you move down the chart, while the last number (elongation) decreases. You’re trading ductility for strength. Pick the grade that matches your actual loading requirements rather than defaulting to “stronger is better.”

Gray iron follows ASTM A48, which classifies materials by minimum tensile strength. Class 20 has 20,000 psi minimum tensile. Class 40 hits 40,000 psi. The SAE J431 spec uses similar logic for automotive applications.

There’s no yield strength or elongation spec because gray iron doesn’t yield or elongate in any measurable way. Design calculations use tensile strength with appropriate safety factors for brittle materials.

ADI takes standard ductile iron and runs it through a specialized heat treatment. The process involves austenitizing at 843-927°C, quenching in molten salt at 232-400°C, and holding at the austempering temperature until transformation completes.

The result is an ausferrite microstructure, a combination of acicular ferrite and carbon-stabilized austenite. ADI achieves tensile strengths over 1000 MPa while maintaining better impact resistance than you’d expect at those strength levels.

Use ADI when you need strength approaching tool steel but want to retain some ductility. Gears, crankshafts, and wear components in mining equipment are common applications. The cost premium over standard ductile iron pays off in extended service life for high-stress parts.

Gray iron makes sense when its specific properties provide real advantages:

The common thread? These applications don’t subject the material to significant tensile stress or impact loading. Gray iron’s brittleness doesn’t matter when the loading is compressive or when the application primarily needs thermal or damping properties.

Ductile iron earns its place when the application demands more than gray iron can deliver:

These applications share a need for tensile strength, impact resistance, or both. Ductile iron handles the loads that would crack gray iron immediately.

When you’re standing in front of a material selection decision, ask these questions:

Will the part see impact or shock loading?

Yes → Ductile iron. Gray iron shatters.

Is vibration damping critical to function?

Yes → Gray iron. Its damping is unmatched.

Does the component contain pressure?

Yes → Ductile iron. No exceptions.

Is the budget extremely tight and loading purely compressive?

Yes → Gray iron works fine and costs less.

Will field welding be required?

Yes → Consider steel. Both irons weld poorly.

Is weight a primary concern?

Yes → Consider aluminum. Iron is heavy.

The fundamentals haven’t changed since Keith Millis discovered ductile iron in 1943. Graphite shape determines mechanical behavior. Flakes concentrate stress and cause brittleness. Nodules distribute stress and enable ductility. Every property difference between these materials traces back to that microstructural reality.

Understanding this relationship lets you make material selections confidently. You’re not guessing based on tradition or defaulting to “whatever we used last time.” You’re matching material properties to application requirements based on engineering fundamentals.

That’s how you avoid both the cracked gray iron component that should have been ductile iron and the expensive ductile iron part that could have been gray iron. Both mistakes are equally wrong, just in different directions.