I’ve seen engineers make expensive mistakes with carbon steel selection. A colleague once specified high-carbon steel for a machine guard, thinking “harder is better.” The first time debris hit it, the guard shattered instead of denting—sending sharp fragments across the shop floor.

That’s the thing about carbon steel. The numbers on a spec sheet only tell half the story. Choosing hardness when you need toughness, or strength when you need weldability, can turn a solid design into a failure waiting to happen.

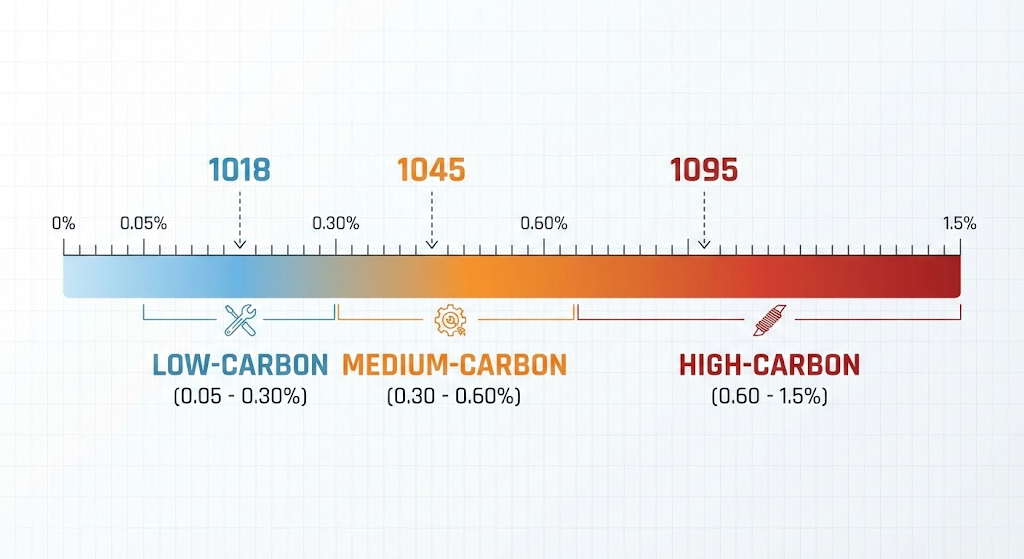

Carbon content is the single biggest factor determining a steel’s mechanical behavior. The AISI/SAE system makes classification straightforward: the last two digits of a grade number tell you the carbon percentage in hundredths.

A 1045 steel contains 0.45% carbon. A 1020 has 0.20%. Simple.

| Classification | Carbon Content | Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Low-Carbon (Mild) | 0.05% – 0.30% | Soft, ductile, excellent weldability |

| Medium-Carbon | 0.30% – 0.60% | Balanced properties, heat treatable |

| High-Carbon | 0.60% – 1.5% | Hard, wear-resistant, brittle |

Low-carbon grades like 1008, 1018, 1020, and A36 dominate the market. They account for over 85% of U.S. steel production because they’re cheap, easy to weld, and form without cracking.

Medium-carbon grades including 1030, 1040, 1045, and 1055 offer the sweet spot between workability and performance. You can heat treat these to significantly boost strength.

High-carbon grades such as 1060, 1075, 1080, and 1095 deliver maximum hardness but sacrifice ductility. Handle these with care during fabrication.

The mechanical properties shift dramatically as carbon content increases. You’re essentially trading ductility for strength with every percentage point.

| Property | Low-Carbon | Medium-Carbon | High-Carbon |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | 400–550 MPa | 600–800 MPa | Up to 1,200 MPa |

| Yield Strength | ~330 MPa (1020) | ~490 MPa (1045) | ~585 MPa (1080) |

| Hardness | <125 HB | 150–200 HB | 60–65 HRC |

| Ductility | High (25%+ elongation) | Moderate (12–18%) | Low (<10%) |

You can’t cheat physics. Every jump in strength comes at the cost of formability.

Low-carbon steel bends, stretches, and welds without complaint. That’s why it works for automotive body panels and structural beams—applications where you need the material to give rather than crack.

High-carbon steel resists deformation but snaps under impact. Perfect for cutting tools and springs. Terrible for anything that sees shock loading.

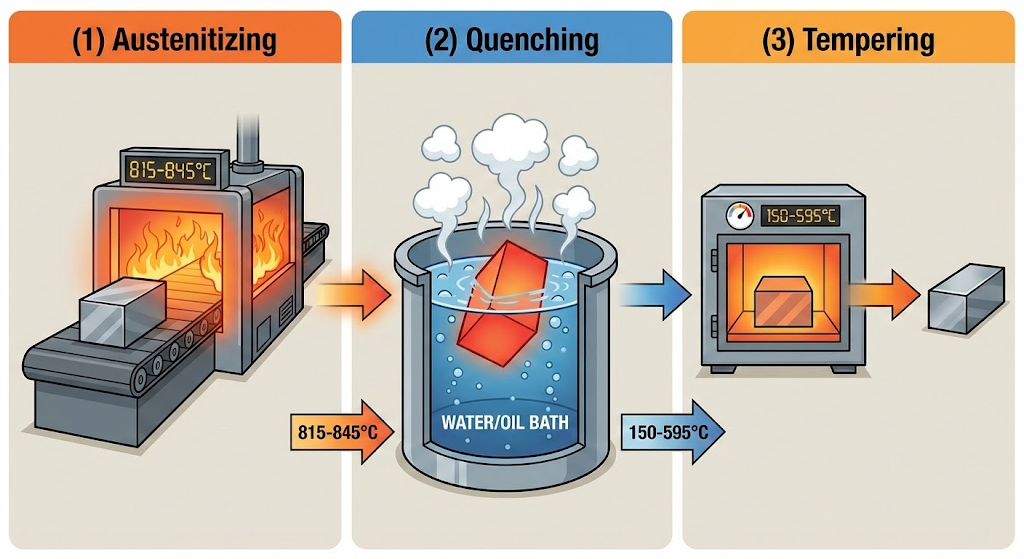

Heat treatment is where carbon content really matters. Below 0.30% carbon, you’re wasting your time trying to harden steel through quenching.

Low-carbon steels can’t form martensite in meaningful amounts. There’s simply not enough carbon to transform the crystal structure during rapid cooling. Surface hardening through carburizing is your only option.

Medium and high-carbon steels respond dramatically to heat treatment. The hardening capability peaks around 0.80% carbon—any higher and you’re just adding brittleness without additional hardness.

| Steel Type | Austenitizing Temp | Quench Medium | Tempering Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medium-Carbon | 815–845°C | Water or oil | 205–595°C |

| High-Carbon | 760–815°C | Oil or water | 150–400°C |

Here’s the critical rule: steel must cool below 538°C (1000°F) in less than one second during quenching. Miss that window and you won’t get full hardness.

Weldability drops as carbon content rises. This isn’t negotiable—it’s metallurgy.

| Carbon Level | Weldability | Primary Concern |

|---|---|---|

| <0.25% | Excellent | None |

| 0.25–0.45% | Good with precautions | HAZ hardening |

| 0.45–0.60% | Difficult | Hydrogen cracking |

| >0.60% | Very difficult | Martensite formation, cracking |

High-carbon steel forms hard, brittle martensite in the heat-affected zone. This creates the perfect setup for hydrogen-induced cracking—sometimes days after welding.

I always err on the side of more preheat. The cost of reheating beats the cost of cutting out cracked welds.

Match the steel to the job, not the other way around. Specifying the “strongest” option often backfires.

| Application | Best Choice | Why |

|---|---|---|

| Structural beams, pipelines | Low-carbon (A36, 1018) | Weldability, ductility, cost |

| Shafts, gears, axles | Medium-carbon (1040, 1045) | Strength + heat treatability |

| Cutting tools, springs, dies | High-carbon (1075, 1095) | Hardness, wear resistance |

Carbon steel selection isn’t about finding the “best” grade. It’s about matching carbon content to your specific requirements.

Need weldability? Go low. Need strength with heat treatability? Go medium. Need hardness and wear resistance? Go high—but respect its limitations.