Mild steel accounts for 85% of all steel production in the United States. That single statistic tells you something important: mild steel is the default choice for most applications.

But here’s where the confusion starts. Mild steel is carbon steel. More specifically, it’s the low-carbon variety of carbon steel – the workhorse grade that handles everything from structural frames to automotive bodies.

The real question isn’t “mild steel or carbon steel.” The choice is between low-carbon (mild) steel and the medium or high-carbon grades that offer hardenability and wear resistance at a higher cost. This guide will help you make that decision based on your actual project requirements.

Mild steel is a subset of carbon steel, not a separate material. All carbon steels contain carbon as the primary alloying element, but the amount of carbon determines which category the steel falls into.

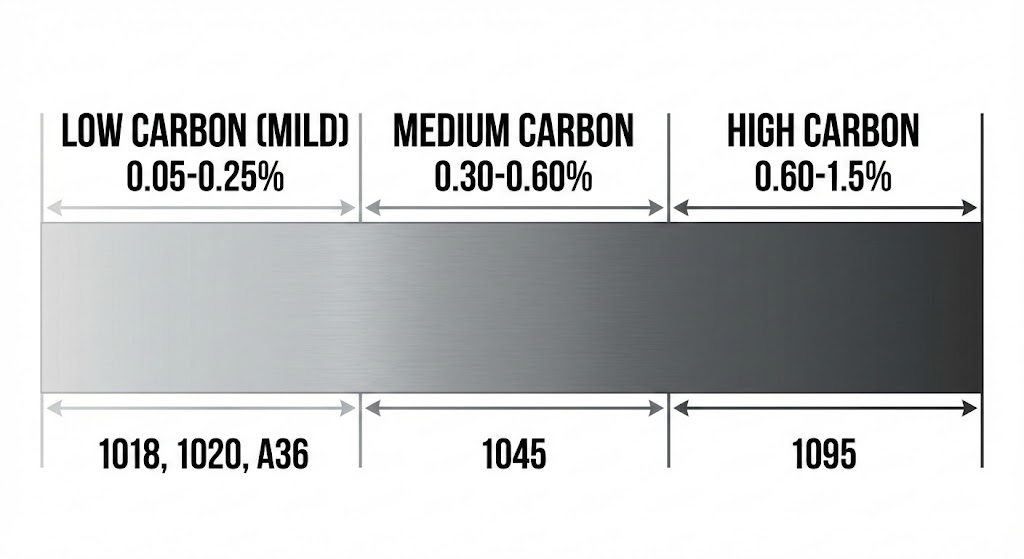

Carbon steel breaks down into three main categories based on carbon content:

| Category | Carbon Content | Common Grades |

|---|---|---|

| Low carbon (Mild) | 0.05-0.25% | 1018, 1020, A36 |

| Medium carbon | 0.30-0.60% | 1045, 1040 |

| High carbon | 0.60-1.5% | 1095, 1080 |

The terminology creates unnecessary confusion in procurement. When someone asks for “carbon steel,” they could mean anything from mild steel to tool-grade material. I recommend specifying the actual grade designation in every RFQ and engineering drawing. “AISI 1018” leaves no room for interpretation; “carbon steel” invites expensive miscommunication.

As one forum contributor put it simply: “1018 or 1020 are mild steel, 1040 is a medium carbon steel, and 1095 is a high carbon steel.” That mental model covers 90% of material selection decisions.

The core trade-off is straightforward: higher carbon content means harder and stronger steel, but with reduced weldability and ductility. Understanding exactly how these properties shift will help you avoid both under-specifying and over-specifying.

Higher-carbon grades can achieve up to 20% greater strength than mild steel. However, this advantage requires heat treatment to fully realize.

| Grade | Type | Yield Strength | Tensile Strength | Hardness |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AISI 1018 | Mild | 370 MPa (54,000 psi) | 400-650 MPa | 126 HB |

| AISI 1020 | Mild | 350 MPa (51,000 psi) | 400-550 MPa | 121 HB |

| ASTM A36 | Mild | 250 MPa (36,000 psi) | 400-550 MPa | – |

| AISI 1045 | Medium | – | 570-700 MPa | 170-210 HB |

Here’s what most specification guides miss: in the as-rolled condition, the strength difference between mild and medium carbon steel is modest. The real advantage of higher carbon appears after heat treatment. If you’re not planning to harden the part, you’re paying a premium for capability you won’t use.

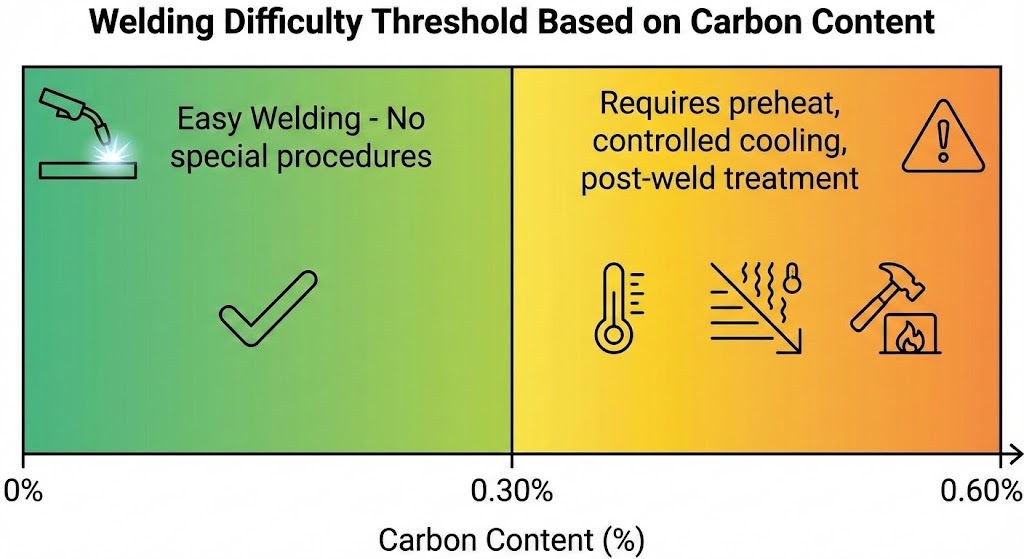

The 0.30% carbon line is where welding gets complicated. Below this threshold, steel welds easily without special procedures. Above it, you’re dealing with preheat requirements, controlled cooling, and potentially post-weld heat treatment.

A practical way to evaluate weldability is the Carbon Equivalent (CE) formula. When CE is 0.35 or below, no pre- or post-weld thermal treatment is needed. Mild steels typically fall well below this threshold, making them straightforward to weld with standard procedures.

If welding is part of your manufacturing process – and for fabricated steel structures, it usually is – the 0.30% carbon threshold should be your first filter. Specifying medium or high carbon steel for a welded assembly adds cost and risk without corresponding benefit unless you specifically need the hardenability.

AISI 1018 exhibits a machinability rating of 78%, while ASTM A36 rates at 72%. These ratings use AISI 1112 free-machining steel as the 100% baseline.

Higher-carbon steels become progressively harder to machine and form. The increased hardness that makes them wear-resistant also makes them resist cutting tools. For parts requiring extensive machining or forming operations, mild steel reduces tool wear and cycle time.

The trade-off summary: mild steel is easier to cut, bend, and weld. Higher-carbon steel resists wear and can be hardened. Choose based on which properties your application actually demands.

Four grades cover the majority of material selection decisions for steel components and castings. Understanding their specific properties prevents both over-specification and under-specification.

| Property | AISI 1018 | AISI 1020 | ASTM A36 | AISI 1045 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carbon Content | 0.18% | 0.17-0.23% | 0.25-0.29% | 0.45% |

| Yield Strength | 370 MPa | 350 MPa | 250 MPa | Higher |

| Tensile Strength | 400-650 MPa | 400-550 MPa | 400-550 MPa | 570-700 MPa |

| Hardness | 126 HB | 121 HB | – | 170-210 HB |

| Machinability | 78% | 72% | 72% | Moderate |

| Weldability | Excellent | Excellent | Excellent | Requires care |

| Heat Treatable | Limited | Limited | No | Yes |

For most structural applications, ASTM A36 is the pragmatic choice. It’s the most commonly specified structural steel in North America, which means every fabricator stocks it, every welder knows it, and every inspector has experience with it. Ubiquity reduces cost and lead time.

When you need higher strength or heat treatability, AISI 1045 is the common step up. It’s used extensively for gears, shafts, and machinery components that need to resist wear. Just accept that welding and machining become more demanding.

Material cost is only part of the equation. The total cost includes fabrication complexity, heat treatment, and the risk of weld failures.

Mild steel averages $600-800 per ton depending on grade, availability, and supplier. Medium and high carbon steels range from $800-1,000 per ton – a 25-35% premium. These figures fluctuate with market conditions, but the relative premium remains consistent.

The hidden costs matter more than the material premium:

My recommendation is direct: don’t pay for hardening capability you’ll never use. The low carbon segment accounts for 90.2% of the carbon steel market by revenue for good reason – it handles most applications at lower cost with fewer complications.

The question isn’t “which is better” – it’s “what does your application actually require.” Start with mild steel as the default, then upgrade only when specific requirements demand it.

Choose mild steel (1018, 1020, A36) when:

Choose medium or high carbon steel (1045+) when:

A useful mental model: only steel high in carbon can be effectively hardened and tempered. If heat treatment isn’t in your manufacturing plan, you’re paying for a capability that won’t deliver value.

For components that need both weldability and wear resistance in different areas, consider specifying mild steel and adding wear surfaces through case hardening, hard facing, or replaceable wear plates. This hybrid approach often costs less than specifying high carbon throughout.

Material selection starts with understanding your actual requirements – not defaulting to the “strongest” option. Now that you understand the relationship between mild steel and higher-carbon grades, you can specify materials that match your application without paying for capabilities you won’t use.

Ready to discuss material requirements for your casting project? Contact our engineering team to review your specifications and recommend the appropriate steel grade for your application.