A food processing equipment manufacturer faced repeated failures in their high-pressure meat grinding cylinders. The forged steel components cracked within months, despite meeting all strength specifications. The fix? Switching to castings. The forged parts failed not because they were weak, but because their strength worked in only one direction while the equipment imposed loads from multiple angles.

This case challenges the conventional wisdom that forging always produces stronger components than sand casting. The real question is not which process is stronger, but which delivers the right strength characteristics for your specific load conditions.

Forged parts genuinely test stronger than cast parts in laboratory conditions. A University of Toledo study found forged steel has 26% higher tensile strength and 37% higher fatigue strength than cast steel.

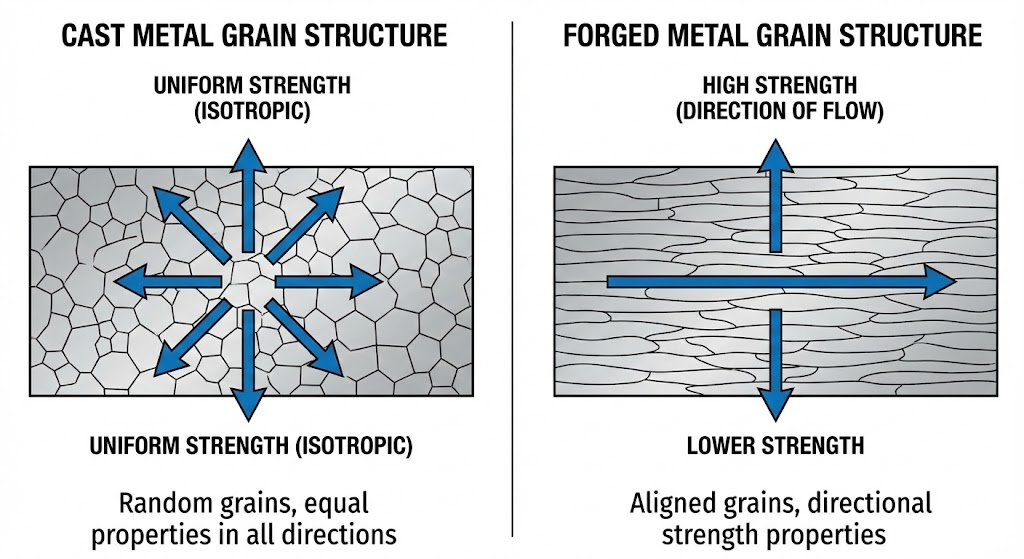

What those comparisons leave out is direction.

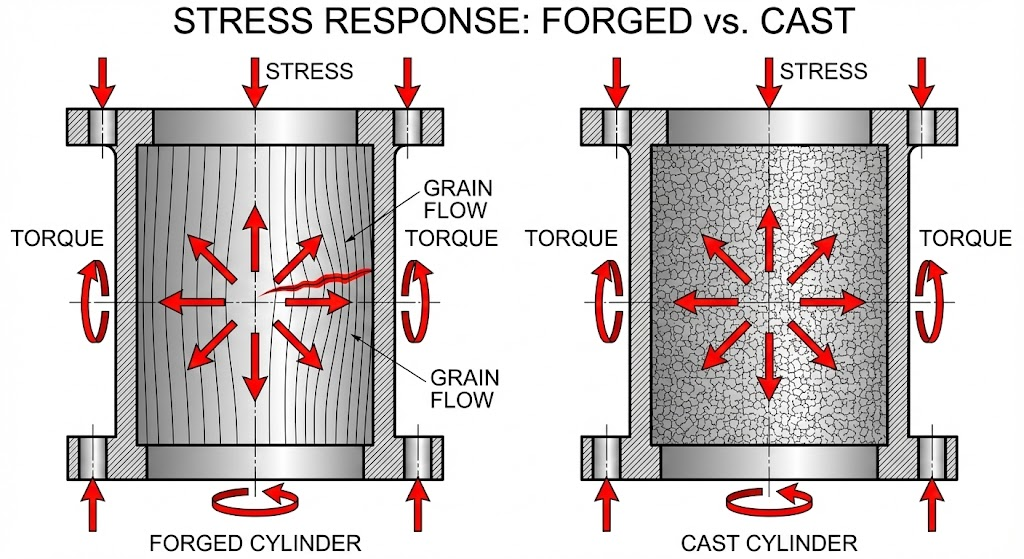

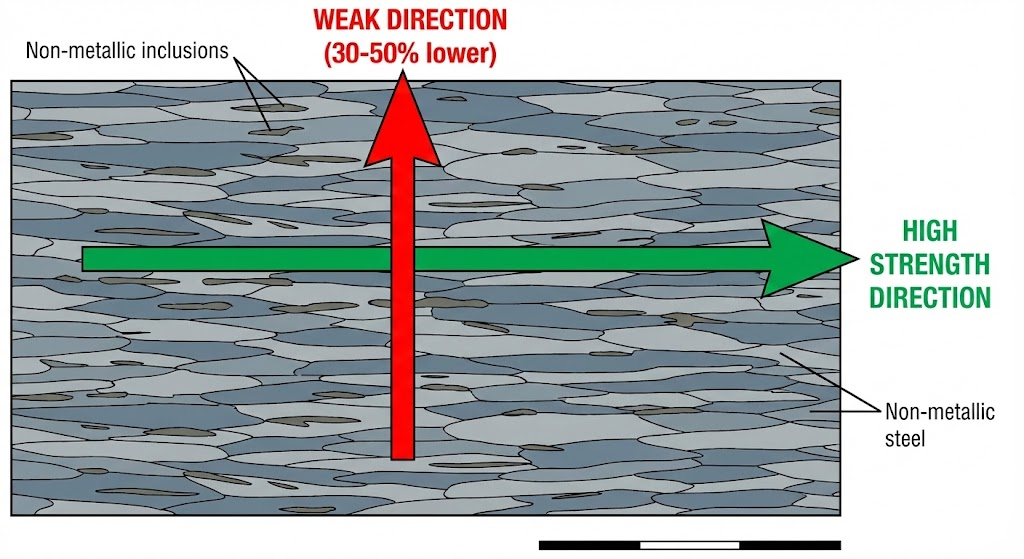

Forging creates aligned grain flow by working the metal under pressure. This grain alignment, plus the elongation of any inclusions in the metal, concentrates strength in the working direction. The result is a part that performs exceptionally well when loaded along that grain flow.

The catch: that same grain alignment creates weakness perpendicular to it. Transverse toughness in forged products runs 30-50% lower than longitudinal values. Fatigue life in the transverse direction drops to less than half of the longitudinal direction, with research showing a 2.3x difference between orientations.

As Gear Solutions magazine noted in a comparative study: “The mechanical properties of a forging are higher in the longitudinal direction… they are significantly lower in the transverse direction, or perpendicular to the grain flow.”

Most real components experience loads from multiple directions during operation. A forged connecting rod sees primary loads along its length, making forging ideal. A valve body sees pressure from inside, torque from actuation, and mounting stresses from all sides, making the directional advantage less relevant.

Engineers designing with forged components must account for this by increasing safety factors 10-15% when transverse properties are critical to the design. That safety margin adds weight and cost.

Sand castings are homogeneous, meaning their mechanical properties remain consistent regardless of stress direction. A casting is best suited to applications subject to multi-axial stresses, where predictable performance in all directions outweighs peak performance in one.

The meat processing equipment succeeded with castings specifically because the grain structure resists both crack initiation and propagation from any direction. Forging’s aligned grain created preferential crack paths under the multi-directional stress environment.

This does not mean castings are always better. Forging remains superior for components with clearly defined, unidirectional primary loads. The key is matching the process to the load pattern.

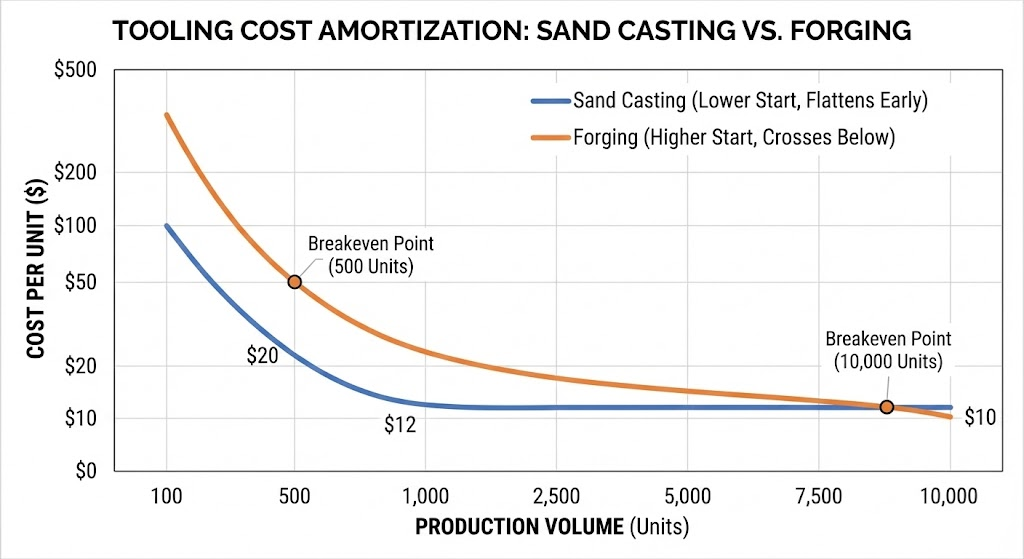

Sand casting and forging have fundamentally different cost structures that favor different production scenarios.

Tooling investment: Sand casting patterns typically cost $500-$7,500 depending on complexity. Closed-die forging tooling runs $2,000-$4,000 for the dies alone, with total tooling packages often higher for complex geometries.

Unit economics: Forging’s economic batch size starts around 500 units for larger components and 10,000 for smaller parts. Below these volumes, the tooling investment becomes difficult to justify.

Sand casting amortizes differently. A $5,000 pattern spread across 1,000 units adds $5 per part. The same pattern over 10,000 units drops to $0.50 per part. This scaling works at lower volumes than forging because the upfront investment is smaller.

Total cost perspective: A defense contractor achieved an average all-in cost reduction of 15% by converting multiple components from forging to casting. The savings came not from lower unit prices, but from reduced tooling investment and qualification costs.

The 26% strength advantage of forging is real, but it costs money. When your application does not require that additional strength, or cannot use it due to multi-directional loading, paying for it wastes budget.

Selection between sand casting and forging depends on matching process capabilities to application requirements.

Unidirectional primary loads: Components like connecting rods, crankshaft throws, and axle shafts experience primary stress along a single axis. Forging’s grain flow alignment delivers maximum strength where you need it.

Impact and fatigue resistance: When components face repeated shock loading in a predictable direction, forging’s aligned structure resists crack propagation along the primary load path.

Maximum strength-to-weight: Aerospace and automotive applications where every gram counts can justify forging’s cost premium for its superior longitudinal properties.

High production volumes: Once you reach 500+ units for large parts or 10,000+ for small parts, forging’s tooling investment amortizes effectively.

Multi-directional loading: Valve bodies, pump housings, and machine frames experience stress from multiple directions simultaneously. Isotropic casting properties provide consistent performance regardless of load angle.

Complex internal geometry: Sand casting can produce internal passages and cavities that forging cannot achieve without extensive machining.

Low to medium volumes: Production runs under 500 large parts or where design changes are likely favor casting’s lower tooling investment.

Large component sizes: Sand casting handles part sizes exceeding practical forging limits. Marine propulsion components, large valve bodies, and industrial equipment housings often exceed forge press capacities.

The trend in some industries confirms this logic. Many crankshafts and connecting rods traditionally made by forging are increasingly produced in ductile iron castings where the load patterns and cost requirements favor casting’s characteristics.

Before defaulting to forging because it is “stronger,” evaluate these factors:

The 26% strength advantage of forging is genuine, but only in one direction. For applications where multi-directional performance matters, sand casting’s isotropic properties often deliver better real-world results at lower total cost.