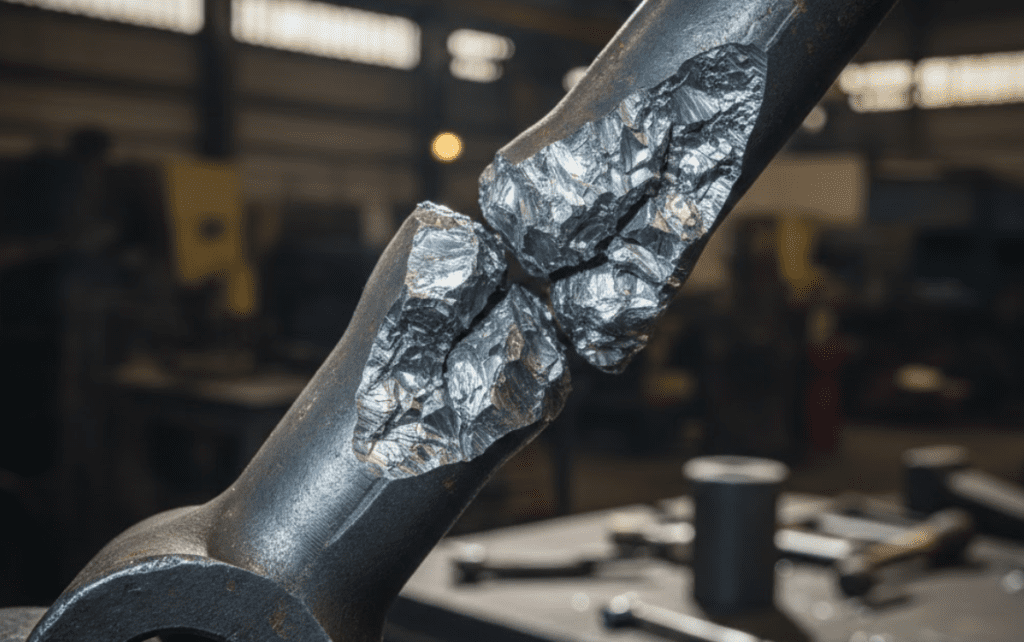

A 1020 steel clevis snapped under pressure during routine operation. The failure analysis revealed carbon content at 0.13%—below the 0.18-0.23% specification—and no heat treatment had been applied. The foundry had delivered exactly what was ordered. The problem was the specification itself.

From a sourcing perspective, this pattern repeats across industries. Engineers debate whether to use carbon, alloy, or stainless steel, but most casting failures I’ve seen trace back to incomplete specifications, not wrong family selection. The steel family gets the blame when the real culprit is under-specification of grade requirements, heat treatment, and mechanical properties.

Choosing carbon, alloy, or stainless is the easy part. The hard part is specifying exactly what you need within that family.

The clevis failure illustrates the gap. The engineer specified “1020 steel” without defining minimum mechanical properties or heat treatment requirements. The foundry produced a chemically compliant part—but one that couldn’t handle the actual service loads.

According to the Steel Founders’ Society of America, “Designers frequently ask for the highest strength material available, but often toughness and fatigue resistance are what is really needed.” Increasing strength normally reduces ductility, toughness, and weldability. A lower-strength grade with proper heat treatment often outperforms a higher-strength grade specified incorrectly.

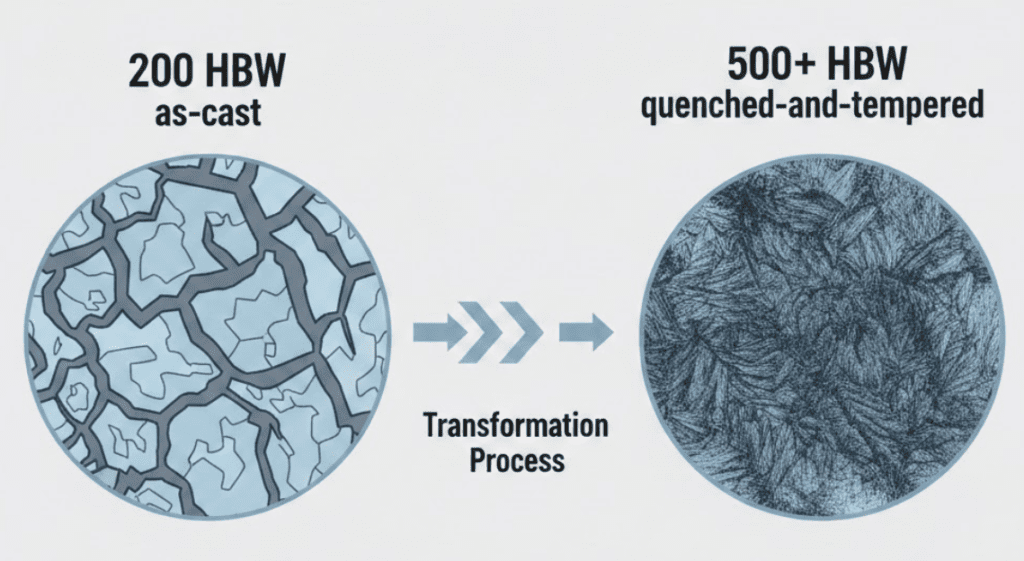

The same alloy can have dramatically different properties depending on heat treatment. Hardness can rise from roughly 200 HBW in the as-cast state to over 500 HBW after quench-and-tempering—a 150% increase from the same chemistry. If your specification doesn’t include heat treatment requirements, you’re leaving performance on the table.

Carbon steel remains the workhorse for sand casting applications. It offers the lowest material cost and adequate properties for most general-purpose applications.

ASTM A216 covers carbon steel castings for high-temperature service. These three grades represent the most commonly specified options:

| Grade | Tensile Strength | Yield Strength | Elongation |

|---|---|---|---|

| WCA | 60-85 ksi (415-585 MPa) | 30 ksi (205 MPa) min | 24% min |

| WCB | 70-95 ksi (485-655 MPa) | 36 ksi (250 MPa) min | 22% min |

| WCC | 70-95 ksi (485-655 MPa) | 40 ksi (275 MPa) min | 22% min |

WCB is the most frequently specified grade, offering a balance of strength and weldability. For simple designs with complex carbon steel requirements, expect pricing around $0.70-$1.18 per pound depending on complexity.

Carbon steel becomes inadequate when your application requires corrosion resistance, elevated temperature service above 450C, or yield strength exceeding 40 ksi. It also struggles in sub-zero temperature applications where impact toughness becomes critical.

Rather than jumping to a different steel family, first consider whether heat treatment can achieve your requirements with carbon steel. Normalizing refines grain diameter from 60 um to 30 um, boosting impact toughness by up to 25%. This modification costs far less than switching to alloy steel.

Alloy steel adds chromium, nickel, molybdenum, or vanadium to carbon steel, achieving higher strength and better hardenability. The cost premium—typically $1.00-$1.50 per pound—is justified when carbon steel cannot meet mechanical property requirements.

ASTM A148 covers high-strength steel castings for structural applications. Strength levels range from 80 ksi to 175 ksi (552-1207 MPa) tensile strength, providing options well beyond carbon steel capabilities.

| Grade | Min Tensile | Min Yield | Min Elongation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 80-50 | 80 ksi | 50 ksi | 22% |

| 105-85 | 105 ksi | 85 ksi | 17% |

| 150-125 | 150 ksi | 125 ksi | 9% |

Higher grades sacrifice ductility for strength. The 150-125 grade delivers nearly double the yield strength of carbon steel WCC but only 9% elongation versus 22%.

Grades 4140 and 8620 are workhorses in alloy steel casting. Both respond well to heat treatment and offer excellent hardenability for medium to large sections.

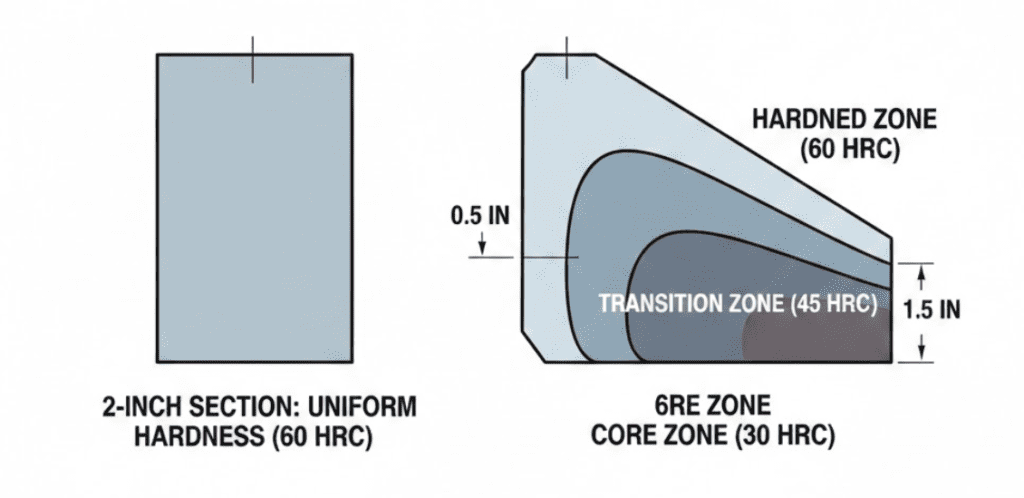

The critical consideration for alloy steel is section thickness. The same grade performs differently at different thicknesses because hardenability limits how deeply the heat treatment penetrates. A 4140 casting with 2-inch sections achieves different properties than one with 6-inch sections—even with identical chemistry and heat treatment cycles.

When specifying alloy steel, include maximum section thickness in your requirements. This allows the foundry engineer to verify hardenability meets your mechanical property needs.

Stainless steel castings require minimum 10.5% chromium by mass, forming the passive oxide layer that resists corrosion. The cost premium is significant—stainless runs 2-3x the price of carbon steel—but the total cost of ownership may favor stainless in corrosive environments.

The CF series covers austenitic stainless steels, the most common choice for corrosive service:

| Cast Grade | Wrought Equivalent | Key Feature |

|---|---|---|

| CF8 | 304 | General corrosion resistance |

| CF3 | 304L | Low carbon for weldability |

| CF8M | 316 | Molybdenum for chloride resistance |

| CF3M | 316L | Low carbon + molybdenum |

CF8M contains 2-3% molybdenum, providing superior resistance to chlorides and pitting corrosion. The “3” grades (CF3, CF3M) limit carbon to 0.03% maximum, improving weldability and resistance to intergranular corrosion.

Expect a 20-30% premium for CF8M over CF8. For marine or chloride-exposed applications, this premium typically pays back through reduced maintenance and longer service life.

Austenitic grades (CF series) offer the best corrosion resistance but cannot be hardened by heat treatment. For applications requiring both corrosion resistance and high hardness—such as valve seats—consider martensitic grades like CA15 or CA6NM.

Martensitic grades achieve hardness through quenching but sacrifice some corrosion resistance compared to austenitic grades. The selection depends on whether your application prioritizes wear resistance or chemical resistance.

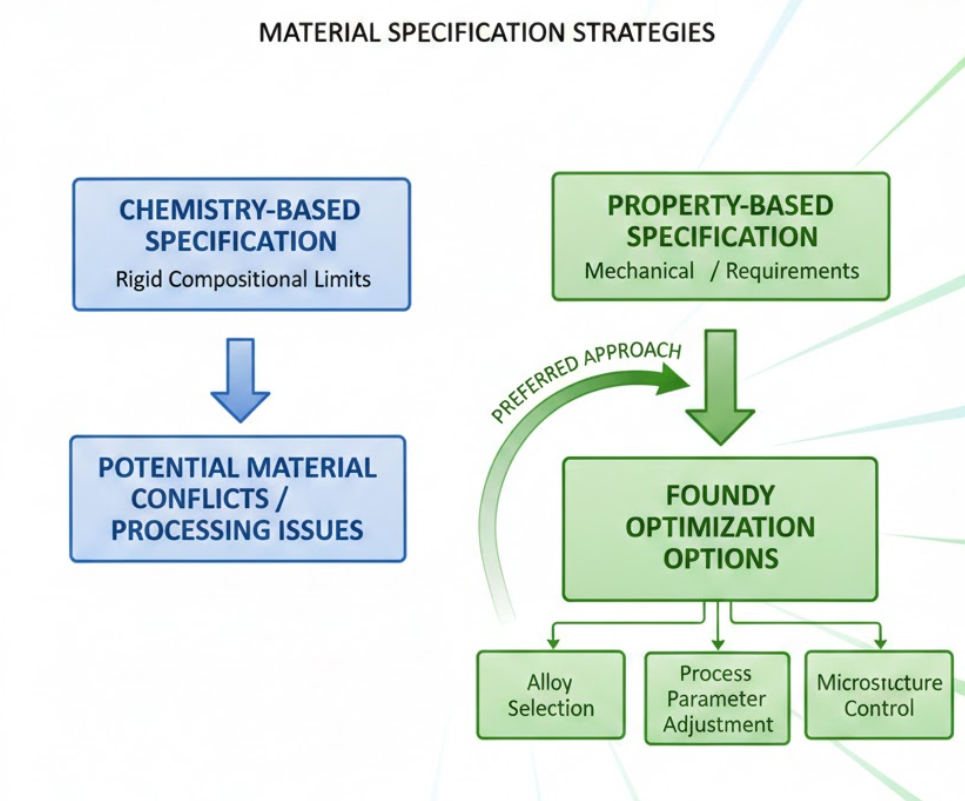

The steel production process allows foundries significant flexibility in achieving specified properties. Your job is to define the outcomes you need; the foundry engineer optimizes the chemistry to achieve them.

According to SFSA, “Steel castings, whenever possible, should be purchased to property requirements rather than to chemical analysis specifications. This permits the foundry engineer to select the alloy compositions which best satisfy mechanical property selection.”

Property-based specification beats chemistry-based specification for three reasons:

Common specification mistakes include conflicting requirements (hardness incompatible with tensile strength), missing heat treatment state, and unspecified testing locations for mechanical properties.

Before requesting quotes, verify your specification includes:

The Steel Founders’ Society recommends three keys to successful specification: utilize the geometry of the steel casting to uniformly carry the loading, start with carbon steel and add complexity only when needed, and know the design limits for the application while working with a metalcasting facility.

The steel family—carbon, alloy, or stainless—is just the starting point. The foundry can’t optimize what you don’t specify.

Start by defining the mechanical properties your application actually requires. Work backward from service conditions: temperature range, corrosion environment, dynamic versus static loading, and required safety factors. Then specify those properties explicitly rather than assuming a grade designation covers them.

When in doubt, specify properties and let the foundry engineer recommend the grade. You’ll get better results than prescribing chemistry and hoping it delivers the performance you need.