Forged parts last up to six times longer than cast equivalents under repeated stress. That single fact explains why every crankshaft in every car on the road is forged, not cast.

Your vehicle contains more than 250 forged components. The crankshaft, connecting rods, wheel spindles, and suspension parts all share one thing in common: they experience repeated stress thousands of times per minute, and they cannot fail.

Forging is a manufacturing process where solid metal is shaped by pressure rather than melted and poured. The result? Parts that are 26% stronger and last dramatically longer than their cast counterparts. This guide explains exactly what forging is, how it works, and when it’s the right choice for your project.

Forging shapes solid metal using compressive force. Unlike casting, the metal never melts. It’s pressed, pounded, or squeezed into shape while remaining solid throughout the process.

Humans have forged metal since 4000 BC in Mesopotamia, making this one of humanity’s oldest manufacturing techniques. Ancient blacksmiths discovered what metallurgists now prove with data: hammered metal outperforms melted metal.

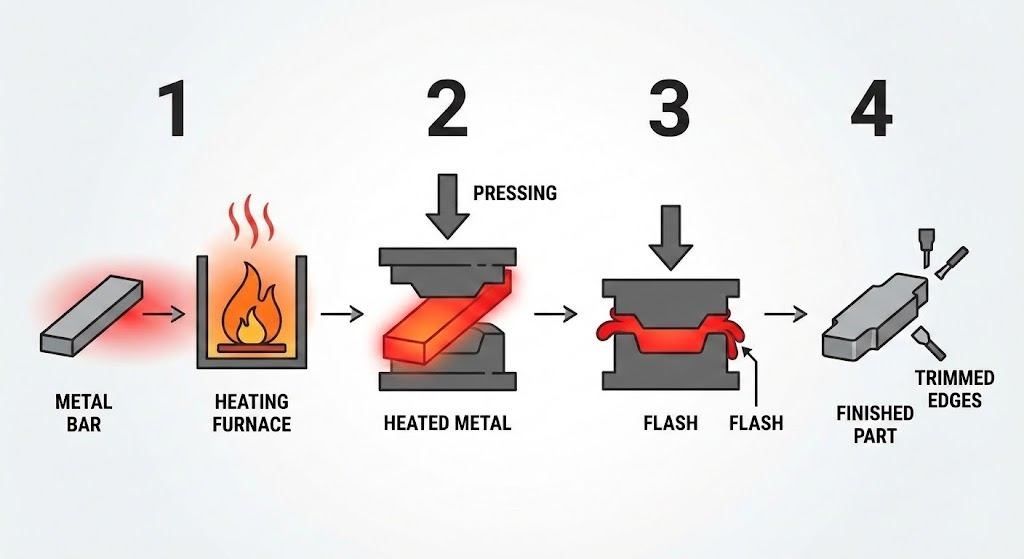

Modern forging follows four fundamental steps.

Heat the Metal. For hot forging, metal is heated until it becomes malleable but not liquid. Steel reaches temperatures up to 1150C. Aluminum alloys stay between 360C and 520C. The metal glows but holds its solid form.

Apply Pressure. The heated metal enters a die or sits under a hammer. Hydraulic presses deliver thousands of tons of force. The metal yields to pressure, flowing into the desired shape.

Shape Forms. Under tremendous force, the metal fills the die cavity. Excess material called “flash” squeezes out around the edges. The grain structure realigns in the direction of the applied force.

Cool and Finish. The part cools and hardens. Flash is trimmed away. Additional machining may add precise features like holes or threads.

Think of forging like shaping clay with your hands—but with metal and tremendous force. The key difference from casting? The metal never becomes liquid. It’s pushed into shape while solid.

Forging methods divide into two main categories: by temperature and by die type. The right combination depends on your part’s size, complexity, and performance requirements.

Temperature determines how easily metal flows and what properties the finished part will have.

| Type | Temperature Range | Best For | Trade-offs |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hot Forging | Above 1150C (steel) | Large parts, complex shapes | More finishing needed, scale formation |

| Warm Forging | 750-950C | Balance of strength and precision | Limited applications, emerging technique |

| Cold Forging | Room temperature to 150C | Small precision parts, high surface quality | Higher tooling costs, limited shapes |

Hot forging dominates industrial applications because heated metal flows easily into complex shapes. Cold forging produces excellent surface finish but requires more force and limits design options. Warm forging occupies a middle ground with what industry experts call “the greatest commercial potential” for steel alloys—though few manufacturers have fully embraced it yet.

The die determines what shapes are possible and at what volume.

Open Die Forging. Metal sits between flat or simple-shaped dies. The operator controls the shape by manipulating the workpiece between hammer strikes. This method handles massive parts—think ship shafts, power generation rotors, and industrial rollers.

Closed Die Forging (Impression Die). Metal fills enclosed die cavities that define the final shape. Excess material squeezes out as flash. This method produces consistent, complex shapes at high volumes—automotive parts, hand tools, and aerospace components.

Seamless Rolled Ring Forging. A specialized process that creates ring shapes by punching a hole in a round blank, then rolling it to expand the diameter while maintaining wall thickness. Bearings, flanges, and gear blanks often use this method.

For most applications, closed die forging offers the best balance of precision, strength, and cost efficiency. Open die makes sense only for very large parts or low volumes where die costs cannot be justified.

Forging shapes solid metal by force. Casting melts metal and pours it into a mold. This fundamental difference determines everything about the finished part’s performance.

Picture the difference this way: forging is like sculpting a block of clay with your hands, while casting is like pouring pancake batter into a mold.

The University of Toledo conducted a comprehensive study comparing forged steel crankshafts to ductile cast iron crankshafts. The results were decisive.

| Property | Forged Parts | Cast Parts | What This Means |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tensile Strength | Baseline | 26% lower | Forged parts handle more pulling force |

| Fatigue Strength | Baseline | 37% lower | Forged parts resist repeated stress better |

| Fatigue Life | Baseline | 6x shorter | Forged parts last dramatically longer |

| Yield Strength | Baseline (forged steel) | 66% (cast iron) | Forged parts deform less under load |

That 6x difference in fatigue life matters most in practice. A component that survives six times more stress cycles doesn’t just last longer—it provides a safety margin that prevents catastrophic failure.

Choose forging when:

Choose casting when:

Most engineers default to casting because it’s versatile and cost-effective. That’s often the right call. But for parts that bear repeated loads and cannot fail? Forging is worth the premium.