3D printing has slashed pattern-making lead times from 3-4 months to just 3-4 weeks. That 90% reduction is reshaping how foundries compete for urgent projects and complex geometries. But whether you choose traditional or digital methods, pattern making remains the critical first step that determines your casting’s quality, cost, and timeline.

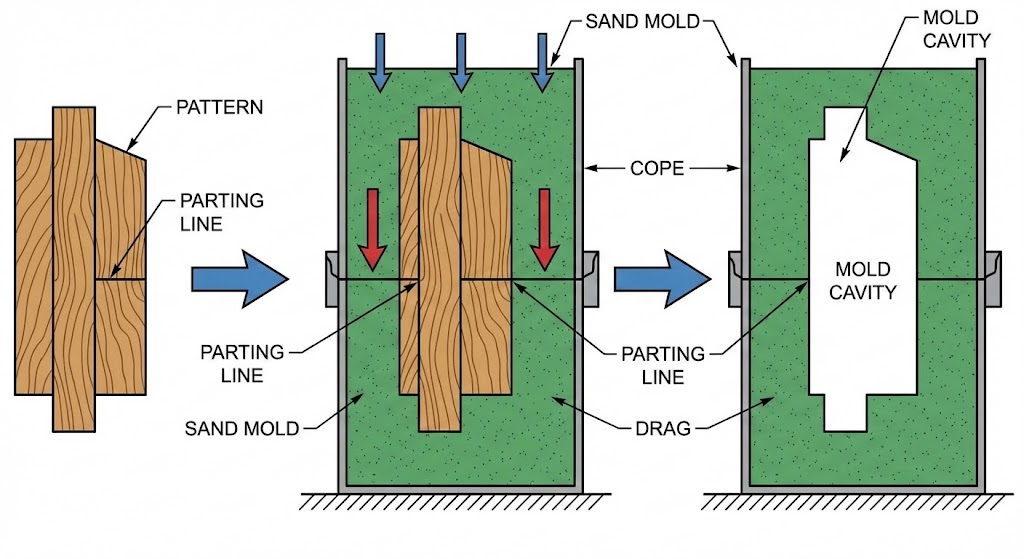

Pattern making is the process of creating a physical model that forms the cavity in a casting mold. When packed in sand, the pattern creates the negative space into which molten metal flows.

A pattern is not an exact replica of the final casting. Pattern makers must modify the original design to account for metal shrinkage during cooling, add draft angles for clean pattern removal, and include extra material for post-casting machining. These modifications, called pattern allowances, determine whether your finished casting meets dimensional specifications.

The pattern-making phase is where most casting projects succeed or fail. A poorly designed pattern leads to defects, rework, and delays. A well-engineered pattern produces consistent castings with minimal post-processing.

Choosing the right pattern type depends on your part geometry, production volume, and budget. Each type offers trade-offs between cost, complexity, and production speed.

Solid patterns are the simplest and lowest-cost option. Made from a single piece of material, they work best for parts with flat parting surfaces and straightforward geometries.

Use solid patterns for prototype runs or annual volumes under 50 pieces. Their main limitation is geometry – if your part has undercuts, internal cavities, or complex features, you need a more sophisticated pattern type.

Split patterns divide along the parting line, with one half forming the cope (top) and the other forming the drag (bottom) of the mold. This design handles complex geometries that solid patterns cannot.

Most production castings use split patterns. They serve as the standard for components like steam valves, pulleys, wheels, and housings with internal features.

Match plate patterns mount both cope and drag halves on opposite sides of a single plate. This configuration enables machine molding and delivers consistent, rapid production.

For high-volume work, match plate patterns justify their higher upfront cost through faster cycle times and improved repeatability. If you order thousands of castings annually, ask your foundry about match plate capability.

Cope and drag patterns use separate plates for each mold half. Unlike match plates, these can be handled independently – critical for large, heavy castings that would be impractical for a single operator.

This pattern type suits large industrial components where precision alignment can be maintained through pins and locating features on each plate.

Loose piece patterns include removable sections that allow the pattern to be extracted from complex mold cavities. Skilled molders remove the main pattern first, then extract loose pieces individually.

Expect higher costs and longer cycle times with loose piece patterns. They require experienced labor and increase the risk of dimensional variation between castings.

| Pattern Type | Best For | Volume Range | Relative Cost |

|---|---|---|---|

| Solid | Simple shapes, prototypes | Very low | Lowest |

| Split | Complex geometries | Low to medium | Low-Medium |

| Match Plate | High-volume machine molding | High | Medium-High |

| Cope and Drag | Large heavy castings | Medium to high | Medium-High |

| Loose Piece | Complex internal features | Low | Highest |

I recommend starting with the simplest pattern type that accommodates your geometry. Over-engineering the pattern adds cost without improving casting quality.

Production volume is the single most important factor in pattern material selection. Industry data provides clear thresholds:

Wood remains popular for prototypes and low-volume production. It costs less, is easy to modify, and pattern makers can produce it quickly. Mahogany, teak, and pine are common choices.

The trade-off is durability. Wood absorbs moisture, warps over time, and wears with repeated use. Store wood patterns in climate-controlled environments and expect periodic refurbishment.

Plastic patterns bridge the gap between wood and metal. They resist moisture, maintain dimensional stability, and handle thousands of molding cycles.

Medium-density tooling boards and polyurethane offer excellent machinability. For production runs in the hundreds to low thousands, plastic often provides the best cost-per-casting economics.

Aluminum and cast iron patterns deliver maximum durability and dimensional consistency. For high-volume production, the higher upfront cost amortizes across thousands of castings.

Metal patterns are heavy and expensive to modify. Avoid investing in metal until your design is frozen and annual volumes justify the investment.

| Material | Volume Range | Key Advantage | Key Disadvantage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wood | Less than 50/year | Low cost, easy to modify | Moisture absorption, warping |

| Plastic/Polyurethane | Up to 5,000/year | Moisture resistant, durable | Can chip or break |

| Metal (Aluminum/Iron) | Over 5,000/year | Maximum durability | High cost, difficult to modify |

For most buyers, my recommendation is straightforward: start with wood for prototypes and first-year production. If volumes grow, upgrade to plastic or metal when the economics make sense.

Pattern allowances are modifications built into the pattern to ensure the finished casting meets specifications. Understanding these allowances helps you review foundry quotes and evaluate their engineering approach.

Metal contracts as it cools from liquid to solid state. Patterns must be oversized to compensate. Different alloys shrink at different rates:

| Metal | Shrinkage Rate |

|---|---|

| Grey Cast Iron | 0.7-1.05% |

| Malleable Iron | 1.5% |

| Steel | 2.0% |

| Stainless Steel | Approximately 2.8% |

| Aluminum Alloys | 1.3-1.6% |

| Brass | 1.4% |

| Bronze | 1.05-2.1% |

If your foundry fails to account for the correct shrinkage rate, every casting will be undersized. Review their shrinkage assumptions during the quote process, especially for tight-tolerance applications.

Draft is the taper applied to vertical surfaces so the pattern can be extracted cleanly from the sand mold. Without adequate draft, removing the pattern damages the mold cavity.

Standard practice applies 1-3 degrees of draft to outer surfaces and 5-8 degrees to inner surfaces. Parts with deep draws or tall features may require more aggressive draft angles.

Most castings require post-casting machining on critical surfaces. Machining allowance adds 2-15 mm of extra material, depending on part size and precision requirements.

Discuss machining allowances early in the quoting process. Excessive allowance increases material cost and machining time. Insufficient allowance leaves no margin for casting variation.

Distortion allowance compensates for warping in castings with irregular cross-sections. Experienced pattern makers anticipate distortion and adjust the pattern geometry accordingly.

Shake (rapping) allowance accounts for the slight enlargement that occurs when foundry workers tap the pattern to release it from the sand.

Pattern making sets the foundation for every successful casting project. The right pattern type, material, and allowances determine whether your parts meet specifications on the first run or require costly rework.

Ready to discuss your casting project? Our engineering team can help you evaluate pattern options, optimize for your production volumes, and develop a tooling strategy that balances cost, quality, and timeline. Contact us to start the conversation.