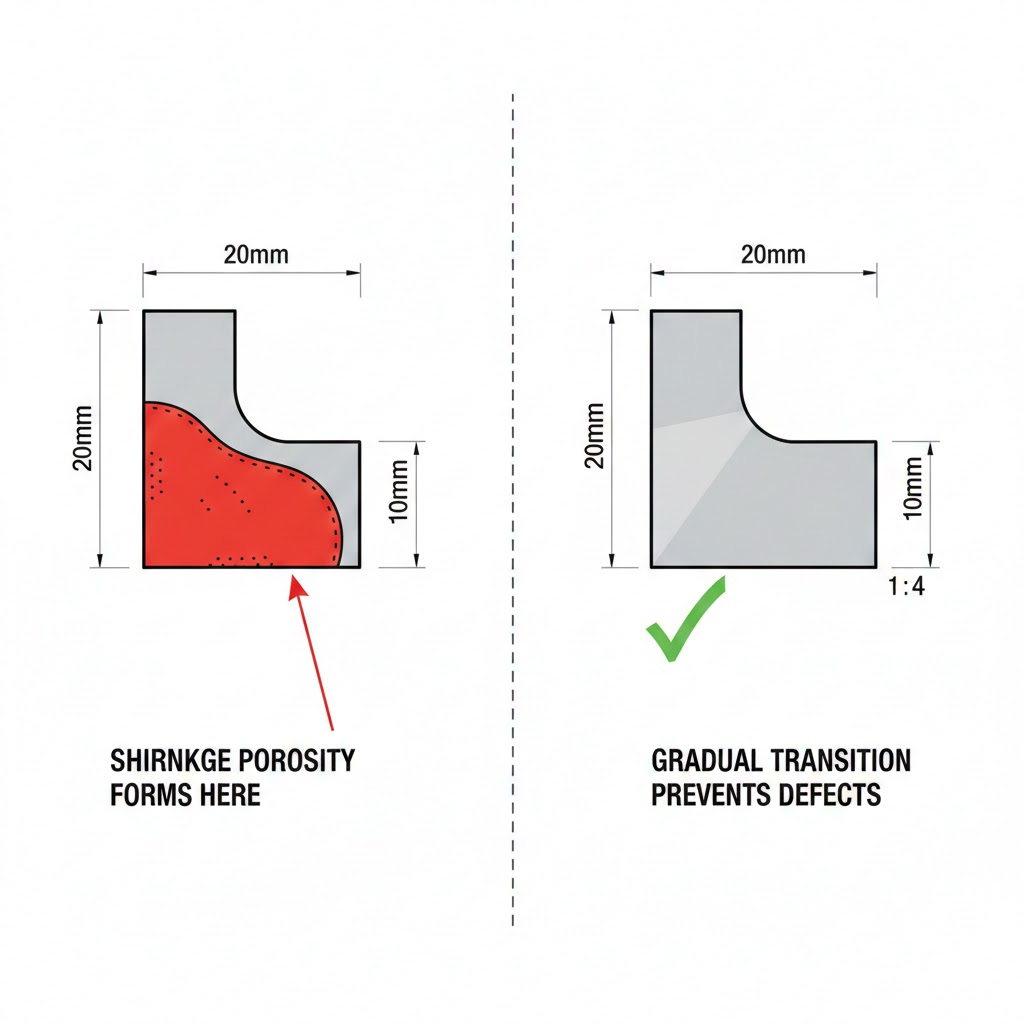

Wall thickness uniformity is the single greatest cause of casting defects. One valve manufacturer traced a 15% rejection rate to uneven wall sections where thick flanges met thinner body walls. After adding gradual transitions and strategic chills, rejections dropped below 2%. The casting itself wasn’t inherently difficult—the design was.

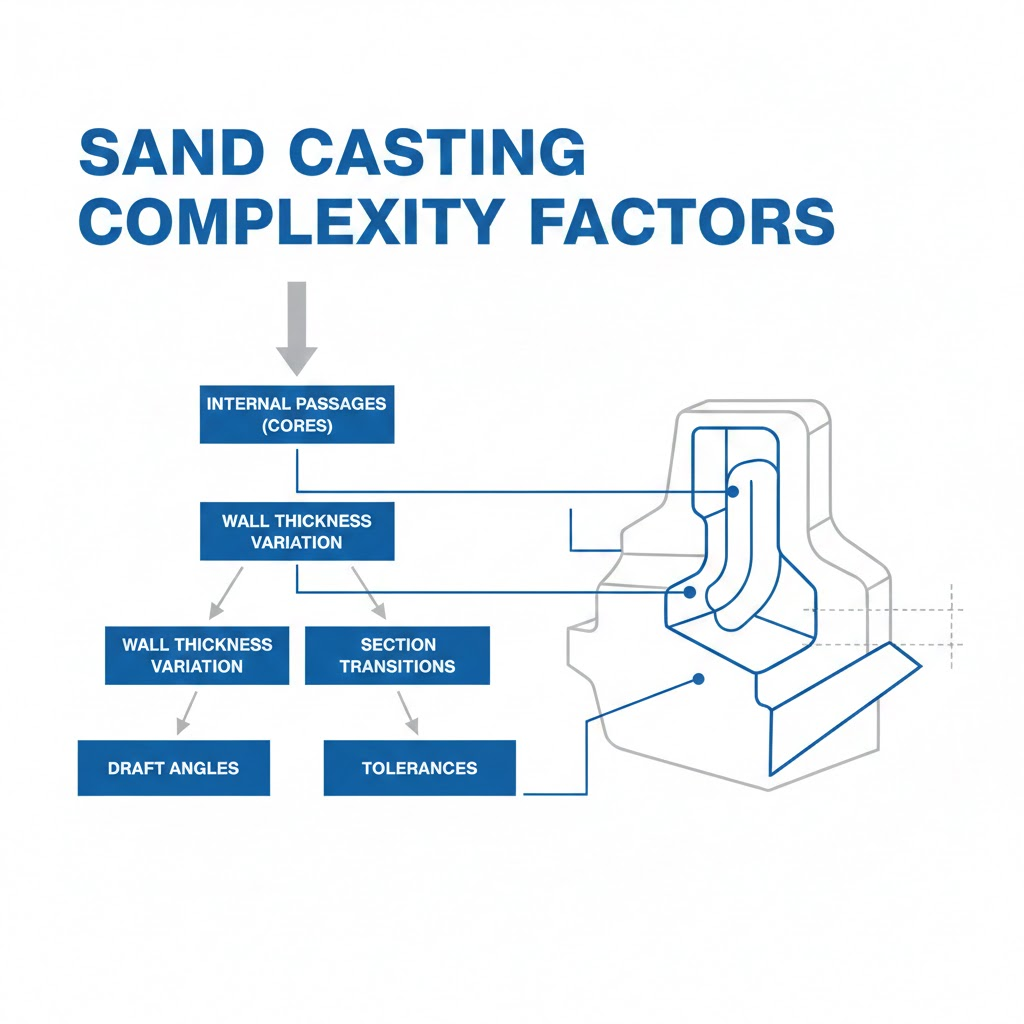

Sand casting difficulty depends on geometry, material selection, tolerance requirements, and internal passage complexity. Understanding where your design falls on each factor determines whether you’re looking at a straightforward production run or a challenging project requiring foundry collaboration.

Sand casting complexity isn’t binary. A part can be simple in geometry but challenging in tolerances, or complex internally while straightforward in material selection. Before designing the pattern, consider how your requirements stack up against standard capabilities.

Dimensional tolerances follow ISO 8062-3 Casting Tolerance (CT) grades. Sand casting typically achieves CT10 through CT14, depending on process type and part size. For practical reference: a 100mm dimension at CT10 means approximately +/-1.1mm variation. Green sand processes generally achieve CT10-CT12, while resin-bonded sand can hit CT8-CT10 for tighter work.

What do these grades mean in practice? A 100mm gray iron bracket cast in green sand at CT8 would hold tolerances of approximately +0.5/-0.4mm. At CT12, that same dimension allows +/-1.8mm. If your design requires tolerances tighter than CT10, you’re either adding machining operations or considering alternative casting methods.

The complexity factors that drive up difficulty include:

Geometry drives most sand casting challenges. The sand casting process requires patterns that can be withdrawn from sand, molten metal that fills all sections before solidifying, and controlled cooling that prevents defects. Each geometric feature affects these requirements.

Minimum wall thickness depends on the alloy’s fluidity—how easily molten metal flows into narrow spaces. Aluminum with its lower viscosity can achieve thinner walls than steel.

| Material | Minimum Wall Thickness | Practical Recommendation |

|---|---|---|

| Aluminum | 2.5 mm (0.10 in) | 4-5 mm for reliability |

| Magnesium | 3.3 mm (0.13 in) | 5 mm minimum |

| Steel | 3.3 mm (0.13 in) | 5-6 mm for ferrous |

| Cast Iron | 3.0 mm | 5-6 mm typical |

Walls under 2mm present significant challenges regardless of material. Metal may not fill completely, or rapid cooling creates hard spots and internal stresses.

More critical than minimum thickness is uniformity. When thick sections connect to thin ones, the thin areas solidify first, cutting off molten metal supply to the thick regions. This creates shrinkage porosity—internal voids that weaken the casting.

The rule of thumb: keep thickness ratios below 2:1 between adjacent sections. When transitions are necessary, use tapers no steeper than 1:4 (4mm length per 1mm thickness change).

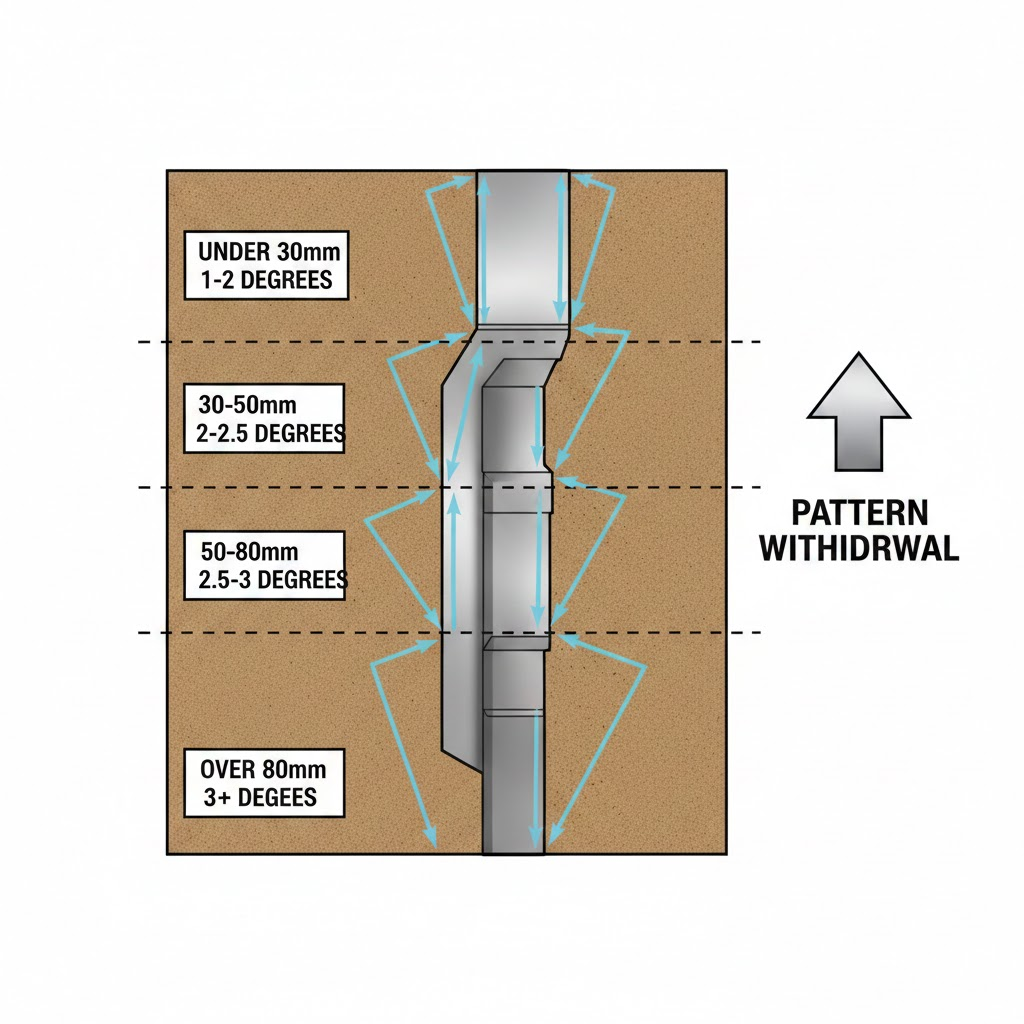

Draft angle—the taper that allows pattern removal—seems straightforward: 1-2 degrees is the standard recommendation. But feature depth changes the requirement.

The draft angle rule of thumb is 2 degrees as baseline, with 1 degree achievable on well-finished surfaces. However, features deeper than 30mm need additional draft. Add 0.25-0.5 degrees per 10mm of height above that threshold. Internal cores typically require an extra 0.5 degrees beyond external surfaces.

| Feature Depth | External Draft | Internal Core Draft |

|---|---|---|

| Under 30 mm | 1-2 degrees | 1.5-2.5 degrees |

| 30-50 mm | 2-2.5 degrees | 2.5-3 degrees |

| 50-80 mm | 2.5-3 degrees | 3-3.5 degrees |

| Over 80 mm | 3+ degrees | 3.5+ degrees |

Zero draft is technically possible only for very shallow features (5-8mm) with mirror-polished pattern surfaces. Avoid designing for zero draft unless absolutely necessary—it sharply increases pattern cost and reduces mold life.

Excessive draft creates its own problems. As one foundry engineer noted, “5 degrees draft suggests you’re being very generous in increasing the part weight and cost.” Extra material means more machining to reach final dimensions.

Sharp corners concentrate stress during solidification and create hot spots where metal remains liquid longest. Fillet radius should equal wall thickness at minimum. For a 10mm wall, use 10mm fillets at inside corners.

Where sections must change thickness, maintain gradual transitions. Maximum recommended ratio is 2:1 between adjacent sections. A 20mm flange connecting to a 10mm wall needs a transition zone, not an abrupt step.

Material selection directly impacts achievable geometry and required allowances. The machining allowance should account for both surface finish requirements and shrinkage variation.

Foundry experts characterize metals by fluidity—how easily they flow into narrow spaces. Nonferrous alloys generally have better fluidity than steels, though cast iron also flows well. This determines what wall thicknesses and detail levels are practical.

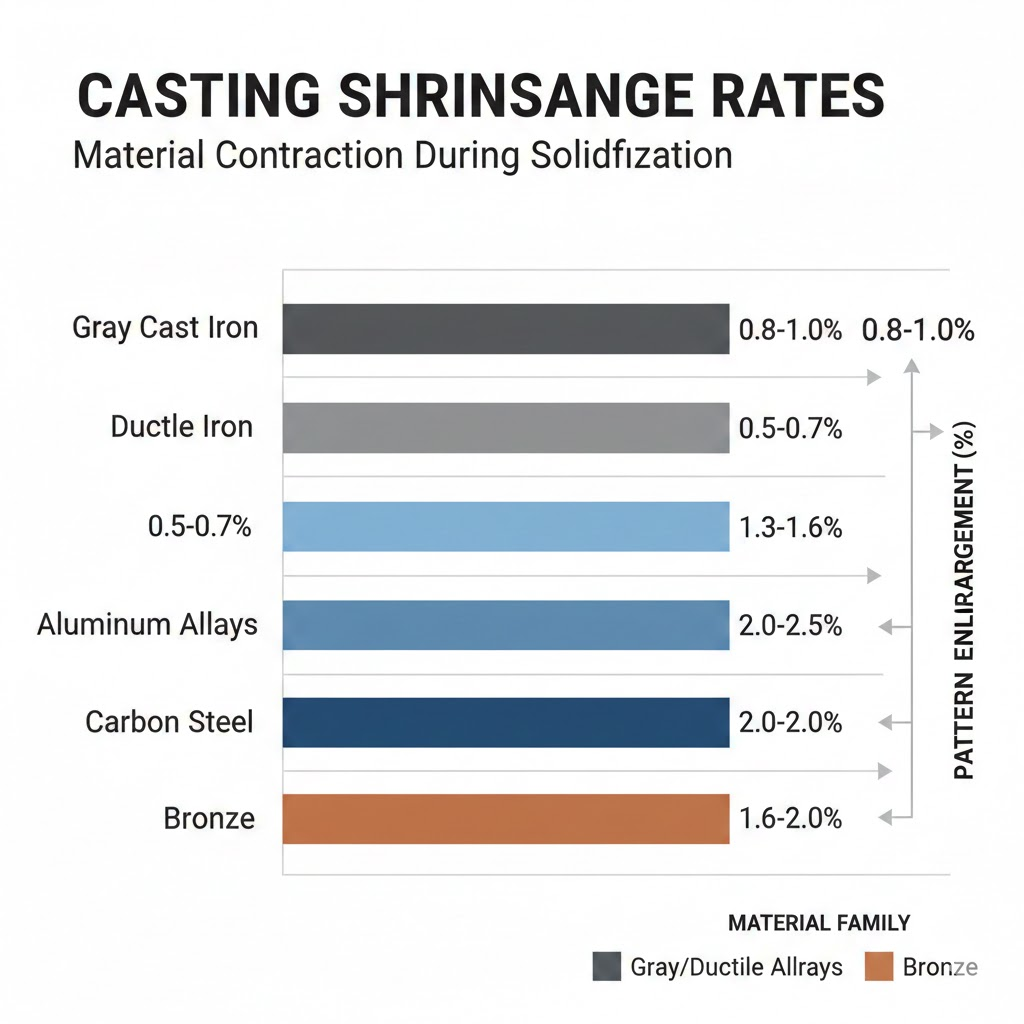

Shrinkage during solidification requires patterns larger than the final part. Each material contracts differently:

| Material | Linear Shrinkage | Pattern Enlargement |

|---|---|---|

| Gray Cast Iron | 0.8-1.0% | 8-10 mm per meter |

| Ductile Iron | 0.5-0.7% | 5-7 mm per meter |

| Aluminum Alloys | 1.3-1.6% | 13-16 mm per meter |

| Carbon Steel | 2.0-2.5% | 20-25 mm per meter |

| Bronze | 1.6-2.0% | 16-20 mm per meter |

Aluminum’s higher shrinkage means tighter attention to feeding—ensuring molten metal can flow to compensate as the casting contracts. Steel’s even higher shrinkage demands strong gating and riser design.

For complex geometries, cast iron’s combination of good fluidity and moderate shrinkage often makes it the easiest material to work with. Steel castings of equivalent complexity typically require more elaborate mold design and tighter process control.

Internal cavities require sand casting cores—shaped sand inserts that create hollow sections. Core complexity is often the largest difficulty multiplier in sand casting.

Simple cores—straight passages, basic pockets—add modest complexity. But internal features introduce four challenges that external geometry doesn’t face:

Core support and positioning. Cores must be held precisely within the mold cavity. Core prints (extensions that seat in the mold) need adequate surface area. Long, unsupported spans can shift during pour.

Wall thickness control. The gap between core and mold determines internal wall thickness. Core shift of even 2mm can create unacceptable thickness variation.

Structural integrity during pour. High-velocity molten metal can erode core surfaces or break thin core sections. Long, slender cores may fuse together if insufficiently supported.

Core removal access. After casting, cores must be removed—typically by shaking, water dissolution, or mechanical knockout. Designs must provide access paths for core material to exit.

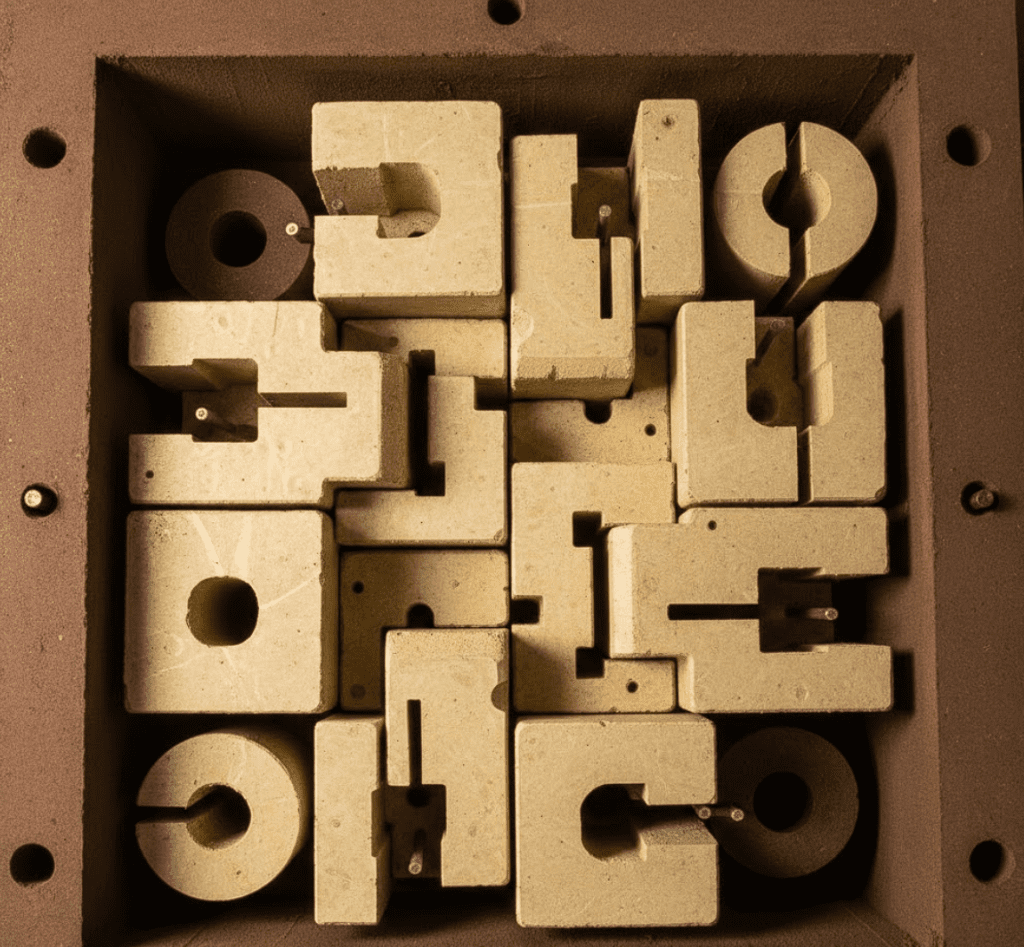

Complex castings sometimes require 20 or more individual cores assembled like a three-dimensional puzzle. Each core adds potential for dimensional variation and defects. When evaluating design complexity, count the cores: one or two is manageable; ten or more signals expert foundry work.

Sand casting handles remarkable complexity, but boundaries exist. Here’s how to specify tolerances correctly for your method selection.

Consider investment casting when:

Sand casting remains preferable when:

Complexity Evaluation Checklist:

Before committing to sand casting, rate your design against these factors:

Three or more “challenging” answers suggests foundry consultation before finalizing design. A capable foundry can often suggest modifications that bring complexity within standard capability—the valve body that dropped from 15% to 2% rejection required only fillet additions and strategic chills, not a complete redesign.

The question isn’t whether sand casting is difficult. It’s whether your specific design aligns with process capabilities. Match your geometry, tolerances, and material to the factors above, and you’ll know before quoting whether the project is straightforward or requires specialized foundry expertise.